The Cuckoo

Edward Thomas

1878 to 1917

That's the cuckoo, you say. I cannot hear it.

When last I heard it I cannot recall; but I know

Too well the year when first I failed to hear it—

It was drowned by my man groaning out to his sheep "Ho! Ho!"

Ten times with an angry voice he shouted

"Ho! Ho!" but not in anger, for that was his way.

He died that Summer, and that is how I remember

The cuckoo calling, the children listening, and me saying, "Nay."

And now, as you said, "There it is," I was hearing

Not the cuckoo at all, but my man's "Ho! Ho!" instead.

And I think that even if I could lose my deafness

The cuckoo's note would be drowned by the voice of my dead.

Edward Thomas's The Cuckoo

Edward Thomas’s "The Cuckoo" is a deceptively simple poem that explores the persistence of memory, the weight of grief, and the way loss reshapes perception. At first glance, the poem appears to be a brief meditation on hearing—or failing to hear—the call of a cuckoo bird. Yet beneath its surface lies a profound examination of how the dead continue to speak, how absence can become louder than presence, and how the past intrudes upon the present in ways that are both haunting and inescapable.

Written during the tumultuous early 20th century, Thomas’s work often reflects the anxieties of his time—the fragility of rural life, the encroachment of modernity, and the specter of war. Though "The Cuckoo" does not explicitly reference the battlefield, its preoccupation with loss and the lingering voices of the dead resonates with the collective mourning of World War I, a conflict that would eventually claim Thomas’s own life. In this analysis, we will examine the poem’s structure, its use of auditory imagery, its engagement with memory, and its emotional impact, situating it within Thomas’s broader body of work and the historical moment in which it was written.

The Illusion of Presence: Hearing and Not Hearing

The poem begins with a moment of failed perception:

That's the cuckoo, you say. I cannot hear it.

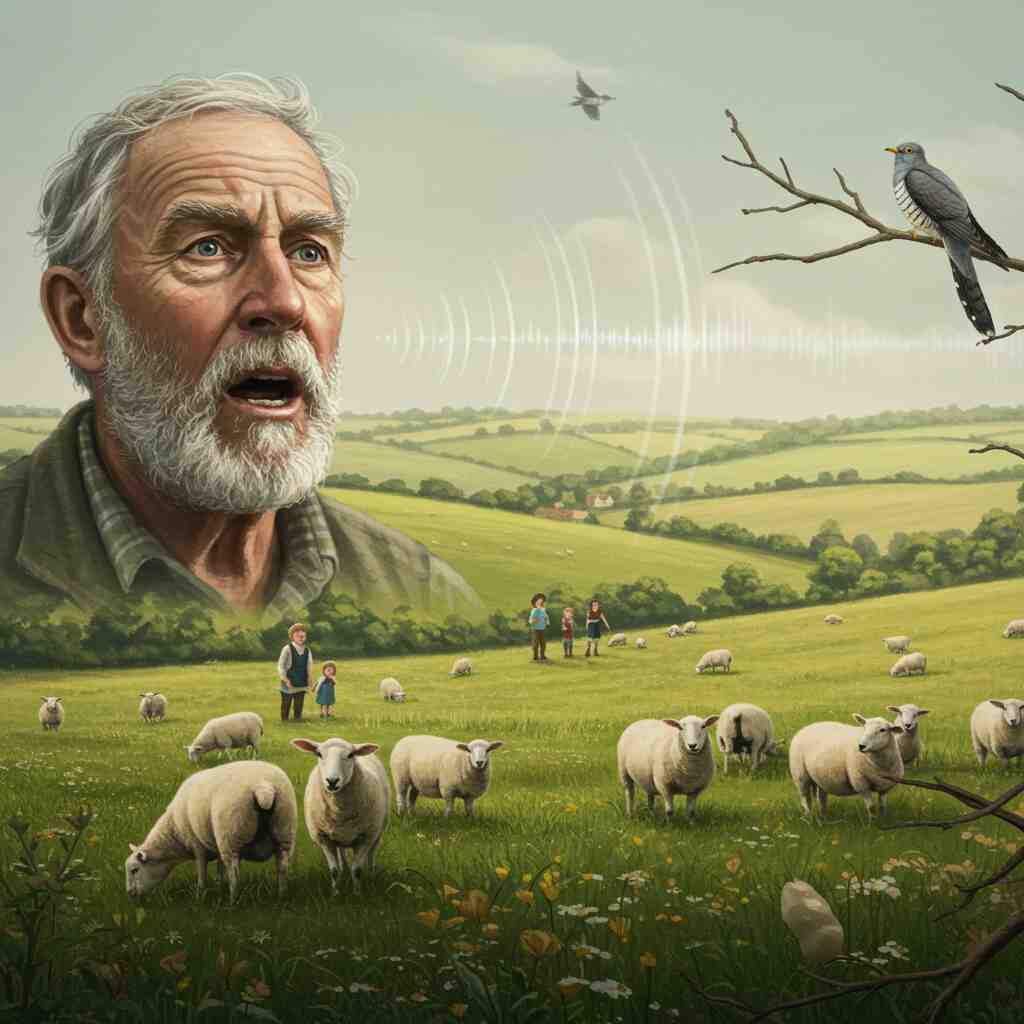

This opening line immediately establishes a disconnect between the speaker and the natural world. While someone else detects the cuckoo’s call, the speaker does not—or perhaps cannot. The cuckoo, traditionally a symbol of spring, renewal, and the cyclical nature of time, should be an unmistakable sound. Yet for the speaker, it is absent, drowned out by something else entirely.

The reason for this auditory displacement is revealed gradually. The speaker recalls a time when the cuckoo’s call was overtaken by a human voice—a man shouting "Ho! Ho!" to his sheep. This memory is not merely an anecdote; it is inextricably linked to death. The man who shouted died that summer, and now, whenever the cuckoo should be heard, the speaker instead hears the echo of the dead man’s voice.

This substitution of sound is one of the poem’s most powerful devices. The cuckoo, a natural and seasonal marker, is replaced by a human utterance, one that carries emotional weight. The poem suggests that grief does not merely obscure the present; it rewrites it. The speaker’s inability to hear the cuckoo is not a failure of the ears but of the mind, which insists on replaying the past even when the present offers something new.

The Persistence of the Dead: Voice as Ghost

The central tension in "The Cuckoo" is between absence and presence. The man is dead, yet his voice remains, so overpowering that it supplants the sounds of the living world. The poem does not merely describe memory; it enacts it. When the speaker says,

And now, as you said, "There it is," I was hearing

Not the cuckoo at all, but my man's "Ho! Ho!" instead.

we see how memory operates as a kind of haunting. The dead man’s voice is not recalled passively; it intrudes, actively replacing the cuckoo’s call. This phenomenon aligns with Sigmund Freud’s concept of "the return of the repressed," where unresolved grief manifests in unexpected ways. The speaker cannot move past the loss, and so the past insists on being heard.

The poem’s closing lines reinforce this idea with devastating clarity:

And I think that even if I could lose my deafness

The cuckoo's note would be drowned by the voice of my dead.

Here, the speaker acknowledges that the issue is not physical deafness but an emotional and psychological saturation. The voice of the dead has become the dominant sound, rendering all others insignificant. This is not just a personal lament but a universal observation about how loss reshapes reality. The dead do not fade; they grow louder.

Historical and Biographical Resonances

Edward Thomas’s own life adds layers of meaning to this poem. Though best known as a poet, Thomas initially wrote prose, often about the English countryside. His work frequently grappled with themes of transience, war, and the erosion of rural life. By the time he turned to poetry in 1914, under the encouragement of Robert Frost, he was already a man deeply attuned to loss—both personal and cultural.

World War I loomed over Thomas’s later years. He enlisted in 1915 and died in the Battle of Arras in 1917. While "The Cuckoo" does not explicitly reference war, its preoccupation with death and the persistence of memory takes on added significance when read in the context of Thomas’s impending fate. The poem’s fixation on a voice that will not fade may reflect the collective trauma of a generation that would soon be defined by its dead.

Moreover, the cuckoo itself carries symbolic weight in English literature. Often associated with fleeting time and unreliable presence (as in the phrase "cuckoo in the nest," suggesting an intruder), the cuckoo’s call is transient, heard only seasonally. The fact that the speaker cannot hear it underscores a rupture in the natural order—time no longer moves forward in the expected way. Instead, the past loops back, inescapable.

Literary Devices and Emotional Impact

Thomas’s language in "The Cuckoo" is restrained yet deeply evocative. The poem avoids elaborate metaphor, relying instead on simple, direct statements that amplify its emotional force. The repetition of "Ho! Ho!" mimics the sound itself, embedding it in the reader’s mind just as it is embedded in the speaker’s. The lack of traditional rhyme or rigid structure gives the poem a conversational tone, making its sorrow feel intimate rather than performative.

The contrast between the cuckoo and the man’s shout is also significant. The cuckoo is a natural, almost mythical presence in English folklore, while the man’s call is human, mundane, yet now irrevocably tied to death. This juxtaposition highlights how grief transforms the ordinary into the monumental. What was once just a shepherd’s shout becomes, in memory, a sound more resonant than birdsong.

Conclusion: The Unheard and the Unforgotten

"The Cuckoo" is a poem about listening—to the world, to the past, to the voices that refuse to be silenced. In its brief lines, Edward Thomas captures the way loss distorts perception, making the absent more vivid than the present. The cuckoo’s call, a symbol of cyclical return, is overpowered by a voice that cannot return except in memory.

In this way, the poem speaks to a universal human experience: the way the dead linger not as shadows but as echoes, louder with time. Thomas, who would soon become one of those echoes himself, crafts a work that is both deeply personal and expansively relatable. The cuckoo may be unheard, but the poem ensures that the man’s voice—and the grief it carries—is not.

Ultimately, "The Cuckoo" is a testament to poetry’s ability to articulate the inarticulable—those moments when the past refuses to release its hold, when memory becomes more real than the living world. In reading it, we are reminded that to grieve is not to forget, but to hear, always, what is no longer there.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem analysis. This exercise is designed for classroom use.