With rue my heart is laden

A.E.Housman

1859 to 1936

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

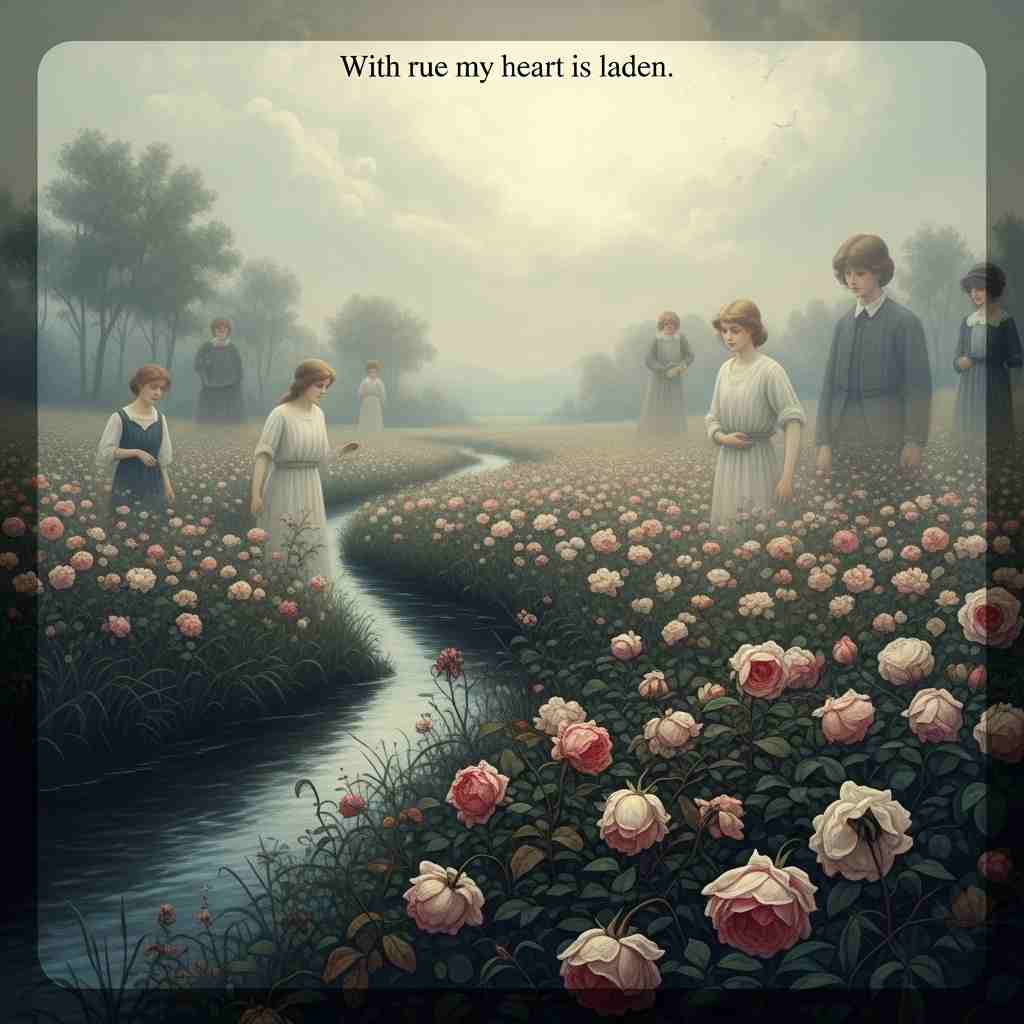

With rue my heart is laden

For golden friends I had,

For many a rose-lipt maiden

And many a lightfoot lad.

By brooks too broad for leaping

The lightfoot boys are laid;

The rose-lipt girls are sleeping

In fields where roses fade.

A.E.Housman's With rue my heart is laden

A.E. Housman’s brief yet profoundly melancholic poem, "With rue my heart is laden," encapsulates the universal human experience of loss, nostalgia, and the inexorable passage of time. Composed in the late 19th century and published in A Shropshire Lad (1896), this poem exemplifies Housman’s characteristic economy of language and his ability to evoke deep emotion through simplicity. Though only eight lines long, the poem resonates with historical, cultural, and philosophical weight, exploring themes of mortality, the fleeting nature of youth, and the irrevocable loss of companionship.

This essay will examine the poem through multiple lenses: its historical and cultural context, its use of literary devices, its central themes, and its emotional impact. Additionally, we will consider Housman’s personal biography and philosophical influences, as well as comparative analysis with other works in the elegiac tradition.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate "With rue my heart is laden," one must situate it within the broader cultural and historical milieu of late Victorian England. The 1890s were a period of transition, marked by the decline of Victorian optimism and the rise of modernist disillusionment. The era was characterized by a growing awareness of mortality, influenced by scientific advancements (such as Darwinism) that challenged religious certainties, as well as by the social upheavals of industrialization.

Housman’s A Shropshire Lad—a collection preoccupied with untimely death, lost love, and the transience of life—reflects this fin-de-siècle anxiety. The poems often depict young men dying in war or fading into obscurity, mirroring the real-life losses of the Boer War (1899–1902) and foreshadowing the devastation of World War I. Though Housman’s poem does not explicitly reference war, its lament for "lightfoot lads" and "rose-lipt maidens" evokes an idealized, pastoral past that has been irrevocably lost—a sentiment that would have resonated deeply with a society on the brink of profound change.

Moreover, Housman’s classical education (he was a renowned scholar of Latin poetry) informs his work. The poem’s brevity and restraint recall the epigrammatic style of ancient Greek and Roman epitaphs, while its meditation on mortality aligns with the carpe diem tradition of Horace and the stoic resignation of Marcus Aurelius.

Literary Devices and Structure

Despite its brevity, "With rue my heart is laden" employs a range of literary devices that amplify its emotional resonance.

1. Symbolism and Imagery

Housman’s imagery is both vivid and economical. The "golden friends" of the past suggest not only warmth and vitality but also the preciousness and rarity of such relationships. The adjective "golden" evokes an idealized, almost mythic quality, reinforcing the sense of irretrievable loss.

The "rose-lipt maidens" and "lightfoot lads" are archetypal figures of youth and beauty, reminiscent of classical pastoral poetry. Yet their fate—sleeping "by brooks too broad for leaping" and in "fields where roses fade"—introduces a stark contrast between vitality and decay. The brooks, traditionally symbols of life and movement, are now barriers ("too broad for leaping"), suggesting the insurmountable divide between the living and the dead. The fading roses, meanwhile, reinforce the poem’s preoccupation with ephemeral beauty.

2. Paradox and Juxtaposition

Housman employs paradoxical imagery to heighten the sense of loss. The "lightfoot boys," once agile and full of life, are now motionless in death. The "rose-lipt girls," whose lips once bloomed like flowers, now rest where roses wither. This juxtaposition of vitality and decay serves as a memento mori, reminding the reader of the inevitability of decline.

3. Alliteration and Assonance

Though this analysis deliberately avoids discussion of rhyme, the poem’s sonic texture contributes to its emotional weight. The alliteration in "lightfoot lads" and "rose-lipt" creates a lyrical, almost musical quality, while the repetition of the long *a* sound in "laid," "maiden," and "fade" produces a lingering, mournful tone.

4. Meter and Rhythm

The poem’s meter (iambic trimeter) lends it a solemn, marching cadence, reinforcing the inevitability of time’s passage. The regularity of the rhythm contrasts with the poem’s thematic chaos—loss, death, and the erosion of beauty—creating a tension between form and content that deepens its impact.

Themes

1. Mortality and the Transience of Youth

The central theme of the poem is the fleeting nature of life, particularly youth. Housman’s depiction of "golden friends" now buried underscores the cruel inevitability of death. The poem does not rage against this fate but instead accepts it with quiet resignation, a hallmark of Housman’s stoic sensibility.

2. Nostalgia and Idealization of the Past

The speaker’s sorrow is not just for the dead but for an irretrievable past. The friends are remembered as "golden," the maidens as "rose-lipt," and the lads as "lightfoot"—all idealized descriptors that suggest an almost mythic past. This idealization heightens the sense of loss, as the present can never measure up to the radiant memory of what once was.

3. Nature as Both Beauty and Tomb

Nature in Housman’s poem is ambivalent: it is the setting of both life (the "brooks" and "fields") and death (where the boys are "laid" and the roses "fade"). This duality reflects the Romantic tradition (seen in Wordsworth and Keats) where nature is both a source of solace and a reminder of mortality.

Emotional Impact

The emotional power of "With rue my heart is laden" lies in its restraint. Unlike more effusive elegies, Housman’s poem conveys grief through understatement. The word "rue" (meaning sorrow or regret) sets the tone immediately, and the subsequent lines unfold with quiet solemnity. There is no dramatic outcry, only a subdued acknowledgment of loss—a technique that makes the poem’s sadness all the more piercing.

The universality of the poem’s themes ensures its enduring resonance. Anyone who has mourned lost friends or the passage of time will find their own grief reflected in Housman’s lines. The poem’s brevity ensures that its emotional weight is concentrated, delivering a swift yet profound impact.

Biographical and Philosophical Insights

Housman’s personal life sheds light on the poem’s melancholic tone. A deeply private man, he experienced significant losses, including the death of his mother when he was twelve and his unrequited love for Moses Jackson, a fellow student at Oxford. His repressed homosexuality in a repressive Victorian society may have contributed to his preoccupation with lost love and unfulfilled desire.

Philosophically, Housman was influenced by Stoicism and classical fatalism. His poetry often reflects a worldview in which suffering is inevitable and must be endured with dignity. "With rue my heart is laden" exemplifies this outlook: the speaker does not seek to escape sorrow but instead acknowledges it with quiet resignation.

Comparative Analysis

Housman’s poem can be fruitfully compared to other works in the elegiac tradition. Thomas Gray’s "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard" similarly meditates on the deaths of ordinary people, though Gray’s poem is more expansive and philosophical. Housman’s brevity, however, makes his lament more immediate and intimate.

Another apt comparison is with the poetry of John Keats, particularly "Ode on Melancholy," which explores the interplay of beauty and decay. Like Housman, Keats acknowledges that joy and sorrow are inextricable—a sentiment encapsulated in Housman’s juxtaposition of "rose-lipt" maidens and "fading" roses.

Conclusion

In just eight lines, "With rue my heart is laden" distills profound grief, nostalgia, and acceptance of mortality. Through its precise imagery, restrained tone, and universal themes, the poem transcends its historical moment to speak to readers across generations. Housman’s fusion of classical restraint and Victorian melancholy creates a work that is both timeless and deeply moving—a testament to the enduring power of poetry to articulate the ineffable sorrows of the human heart.

The poem does not offer consolation, nor does it seek to. Instead, it stands as a quiet monument to loss, inviting the reader to pause, remember, and—like the speaker—carry their rue with dignity. In this way, Housman’s minimalism achieves maximal emotional depth, proving that the most enduring elegies are often the briefest.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!