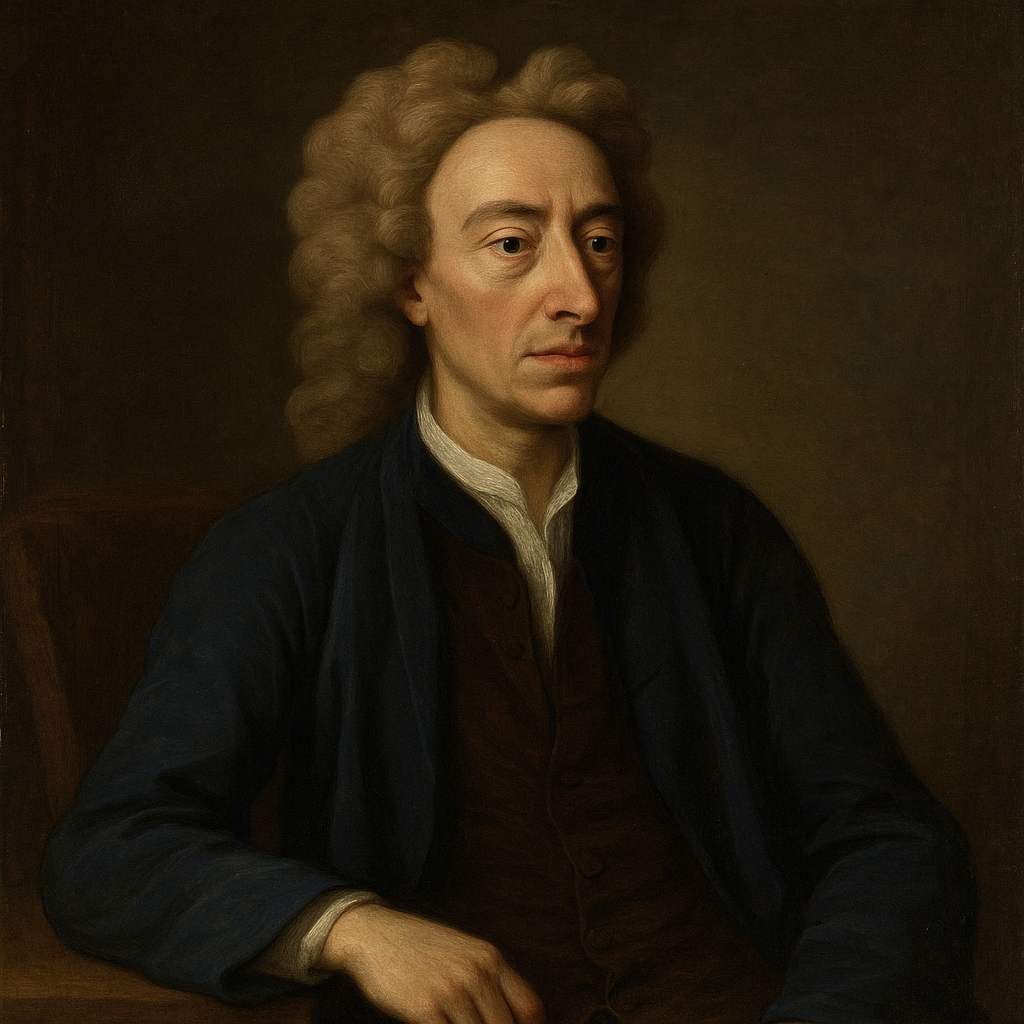

2 Poems by Alexander Pope

1688 - 1744

Alexander Pope Biography

Alexander Pope (1688-1744) emerged as arguably the most significant English poet of the 18th century, masterfully embodying the Augustan age's ideals while pushing the boundaries of poetic form and satire. Born to Catholic parents in London during a period of intense anti-Catholic sentiment, Pope's early life was marked by both privilege and restriction. His father, a successful linen merchant, provided him with access to education, though the Papist Acts barred him from attending university or settling within ten miles of London - constraints that would shape his outsider perspective and fuel his satirical wit.

A childhood illness, likely Pott's disease, left Pope with severe physical disabilities, including a curved spine and stunted growth that reached only 4'6" in adulthood. Yet these physical limitations perhaps concentrated his intellectual energies. Largely self-taught, he immersed himself in classical literature, mastering Latin and Greek while cultivating relationships with prominent literary figures of his day. By age twelve, he had written his first significant poem, "Ode to Solitude," displaying the precocious talent that would later revolutionize English verse.

Pope's breakthrough came with "An Essay on Criticism" (1711), written when he was only 23. This work established his mastery of the heroic couplet and demonstrated his extraordinary ability to compress complex literary and philosophical ideas into memorable, epigrammatic verses. Lines such as "A little learning is a dangerous thing" and "To err is human, to forgive divine" have transcended their original context to become part of common parlance.

His translation of Homer's Iliad, published between 1715 and 1720, transformed him from a respected poet into a wealthy man. This financial independence allowed him to purchase his famous villa at Twickenham, where he created an elaborate garden that reflected his poetic principles of ordered nature and harmonious design. The garden, with its famous grotto, became a physical manifestation of his aesthetic philosophy and a gathering place for the literary elite.

The 1720s saw Pope at the height of his creative powers. "The Rape of the Lock" (1712, revised 1714), his mock-heroic masterpiece, transformed a trivial social slight into an epic commentary on the vanities and vacuities of high society. Its blend of delicate satire and genuine pathos, adorned with supernatural machinery in the form of sylphs and gnomes, created a new kind of poetry that was both playful and profound.

His relationships with contemporaries were complex and often contentious. His friendship with Jonathan Swift resulted in the Scriblerus Club, a literary group that savagely satirized pedantry and poor writing. Yet Pope's sharp tongue and quick wit made him numerous enemies, particularly among the "dunces" he satirized in "The Dunciad" (1728, revised 1743). His romantic life, though never fulfilled in marriage, included several significant relationships, most notably with Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and Martha Blount, the latter remaining his close companion until his death.

"An Essay on Man" (1733-34) represents Pope's most ambitious philosophical work, attempting to "vindicate the ways of God to man" through a comprehensive exploration of humanity's place in the universal order. Though its philosophical arguments have been criticized, its poetic excellence and memorable phrases like "Hope springs eternal in the human breast" have ensured its lasting influence.

Pope's mastery of form, particularly the heroic couplet, transformed English poetry. His ability to balance antithetical ideas within the strict confines of rhyming pentameter couplets created a style that dominated English poetry for nearly a century. His influence extends beyond mere technique; his commitment to classical values, his sophisticated use of irony, and his belief in poetry as a moral force continue to resonate.

In his later years, despite increasing physical pain and social isolation, Pope continued to revise and perfect his work. The final version of "The Dunciad" (1743), with its apocalyptic vision of cultural collapse, stands as a testament to his undiminished creative powers. He died on May 30, 1744, leaving behind a body of work that redefined English poetry and established him as one of literature's most quotable authors.

Pope's legacy lies not only in his individual works but in his demonstration that English could achieve the clarity, wit, and philosophical depth of classical languages. His poetry's formal perfection, intellectual complexity, and moral seriousness created a standard against which subsequent English poetry would be measured. Modern critics have increasingly appreciated the tension in his work between Augustan order and subversive imagination, between classical restraint and baroque complexity, revealing him as a figure who both epitomized and transcended his age.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Username Information

No username is open

Everything is free to use, but donations are always appreciated.

Quick Links

© 2024-2025 R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody).

All music on this site by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Attribution Requirement:

When using this music, you must give appropriate credit by including the following statement (or equivalent) wherever the music is used or credited:

"Music by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) – https://v2melody.com"

Support My Work:

If you enjoy this music and would like to support future creations, your thanks are always welcome but never required.

Thanks!