Sir, I admit your general rule

Alexander Pope

1688 to 1744

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

Sir, I admit your general rule,

That every poet is a fool.

But you yourself may serve to show it,

Every fool is not a poet.

Alexander Pope's Sir, I admit your general rule

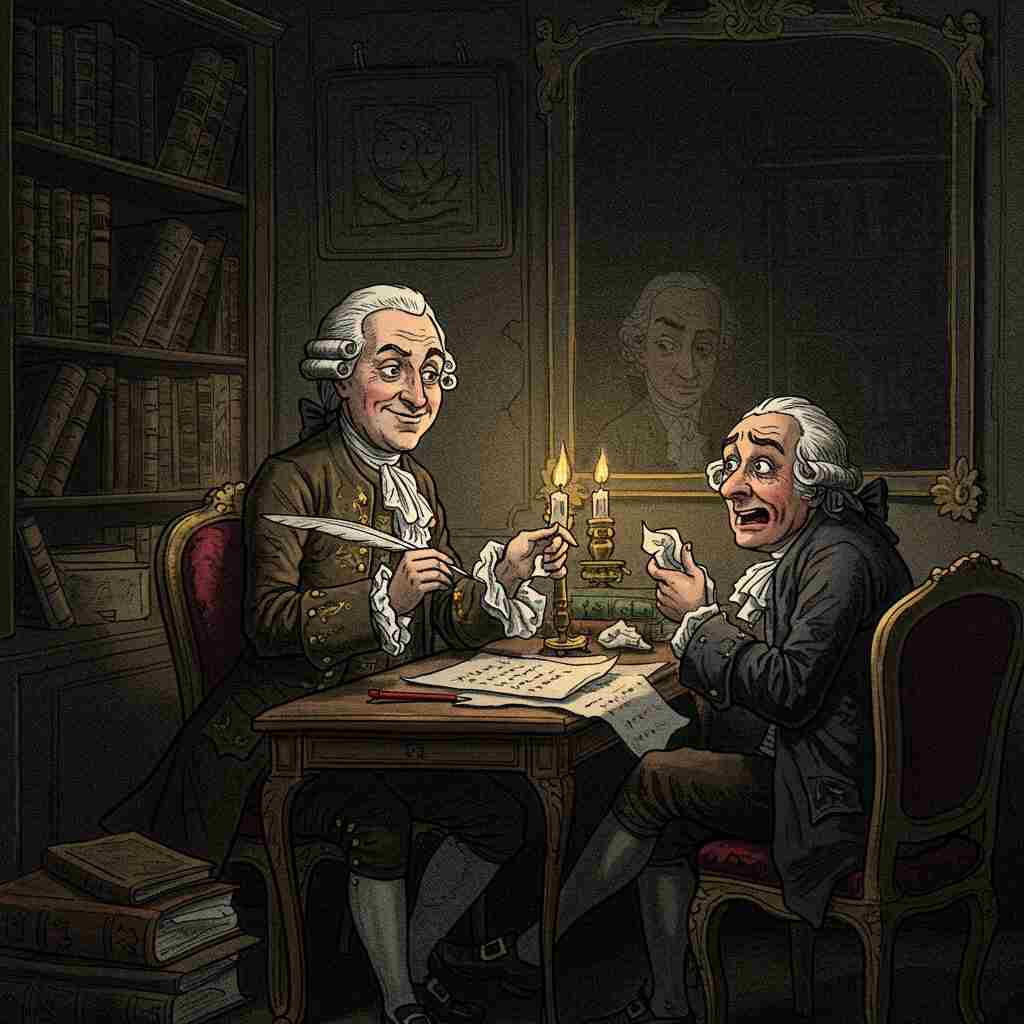

Alexander Pope’s epigram, “Sir, I admit your general rule,” is a deceptively simple yet profoundly incisive piece of poetry that encapsulates the wit, irony, and intellectual rigor characteristic of Pope’s work. Composed in the early 18th century, this poem reflects the cultural and literary milieu of the Enlightenment, a period marked by a fascination with reason, satire, and the interplay between intellect and folly. At only four lines long, the poem is a masterclass in concision, using brevity to deliver a sharp critique of both poetic pretension and intellectual arrogance. Through its clever structure, biting humor, and layered meaning, the poem invites readers to reflect on the nature of art, creativity, and human folly.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate Pope’s epigram, it is essential to situate it within its historical and cultural context. The early 18th century was a time of significant social and intellectual change in England. The Enlightenment was in full swing, emphasizing reason, science, and empirical inquiry. However, this period was also marked by a tension between the ideals of rationality and the persistence of human folly. Satire, as a literary form, flourished during this time, serving as a tool for social critique and moral instruction. Writers like Jonathan Swift, John Dryden, and Alexander Pope used satire to expose the absurdities and hypocrisies of their age.

Pope himself was a central figure in this literary movement. His works, such as The Rape of the Lock and The Dunciad, are renowned for their satirical brilliance and their exploration of human vanity and pretension. Pope’s physical disabilities and his status as a Catholic in a predominantly Protestant England also shaped his perspective, making him an outsider who was acutely aware of societal flaws. This context is crucial for understanding the tone and intent of the epigram in question. The poem is not merely a witty retort but a reflection of Pope’s broader engagement with the follies of his contemporaries and the nature of artistic creation.

Literary Devices and Structure

Despite its brevity, the poem is rich in literary devices that enhance its meaning and impact. The most striking feature is its use of irony. The speaker begins by ostensibly agreeing with a “general rule” that “every poet is a fool.” This statement, delivered with a tone of mock deference, sets up the poem’s central irony. By admitting the rule, the speaker appears to concede a point, but this concession is quickly revealed to be a setup for a more biting observation. The twist comes in the final line, where the speaker asserts that “every fool is not a poet.” This reversal subverts the initial premise, suggesting that while poets may indeed be fools, folly alone does not suffice to make one a poet.

The poem’s structure is also worth noting. It is composed in a closed couplet form, a hallmark of Pope’s style. The couplet’s tight rhythm and rhyme scheme contribute to the poem’s sense of precision and balance. Each line is meticulously crafted, with no wasted words or extraneous details. This economy of language is central to the poem’s effectiveness, as it allows the final line to land with maximum impact. The brevity of the poem also mirrors its thematic focus on wit and concision, contrasting the speaker’s sharp intellect with the broader folly he critiques.

Another key device is the use of antithesis, or the juxtaposition of contrasting ideas. The poem sets up a binary between poets and fools, only to complicate this binary in the final line. This interplay between similarity and difference underscores the poem’s exploration of the relationship between creativity and folly. By suggesting that not all fools are poets, the poem implies that poetry requires something more than mere foolishness—perhaps a spark of genius, a capacity for self-awareness, or a mastery of language.

Themes and Interpretation

At its core, the poem explores the tension between art and folly, creativity and stupidity. The “general rule” introduced in the first line reflects a common stereotype of poets as dreamers and eccentrics, disconnected from the practical concerns of the world. This stereotype has a long history, dating back to classical antiquity, where poets were often seen as inspired but irrational figures. Pope’s poem engages with this tradition, but it does so with a critical edge. By admitting the rule only to qualify it, the poem challenges the reader to reconsider the nature of poetic genius.

One possible interpretation is that the poem is a defense of poetry against its detractors. The speaker’s admission of the “general rule” can be read as a strategic concession, acknowledging the flaws and follies of poets while asserting the value of their craft. The final line, “Every fool is not a poet,” suggests that poetry requires a unique combination of qualities—imagination, skill, and perhaps a touch of madness—that not everyone possesses. In this sense, the poem can be seen as a celebration of the poet’s role as a creator and a thinker, even as it acknowledges the potential for folly within the artistic temperament.

Another interpretation is that the poem is a critique of intellectual arrogance. The unnamed “Sir” who posits the “general rule” is portrayed as a figure of authority, perhaps a critic or a philosopher who dismisses poetry as mere foolishness. The speaker’s response undermines this authority, suggesting that the critic’s own folly disqualifies him from passing judgment on poets. This reading aligns with Pope’s broader satirical project, which often targeted the pretensions of the learned and the powerful. The poem thus becomes a subtle assertion of the poet’s superiority, not despite his folly but because of his ability to transcend it.

Emotional Impact and Universal Appeal

While the poem is intellectually dense, it also has a strong emotional resonance. Its humor and wit make it immediately engaging, while its underlying themes invite deeper reflection. The poem’s exploration of folly and creativity speaks to a universal human experience: the tension between our aspirations and our limitations. Everyone, at some point, has felt the sting of being dismissed or misunderstood, and the poem’s defense of the poet’s role can be seen as a defense of all those who strive to create something meaningful in the face of criticism or indifference.

The poem’s emotional impact is also tied to its brevity and clarity. Unlike longer, more complex works, this epigram delivers its message with a single, sharp stroke. This immediacy makes it accessible to a wide audience, even as its layered meanings reward repeated readings. The poem’s humor, too, contributes to its appeal, as it allows readers to laugh at the absurdities of human nature while also recognizing their own potential for folly.

Conclusion

Alexander Pope’s epigram, “Sir, I admit your general rule,” is a masterpiece of wit and concision. Through its clever use of irony, antithesis, and structure, the poem explores the complex relationship between art and folly, creativity and stupidity. Situated within the historical and cultural context of the Enlightenment, the poem reflects Pope’s broader engagement with the follies of his age and his defense of the poet’s role as a creator and a critic. At the same time, the poem’s humor and emotional resonance make it a timeless reflection on the human condition.

In just four lines, Pope captures the essence of his satirical genius, delivering a message that is both intellectually stimulating and deeply relatable. The poem reminds us that while folly may be universal, the ability to transform that folly into art is a rare and precious gift. In this way, Pope’s epigram not only critiques the follies of its time but also celebrates the enduring power of poetry to illuminate, challenge, and inspire.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more