Ode on Solitude

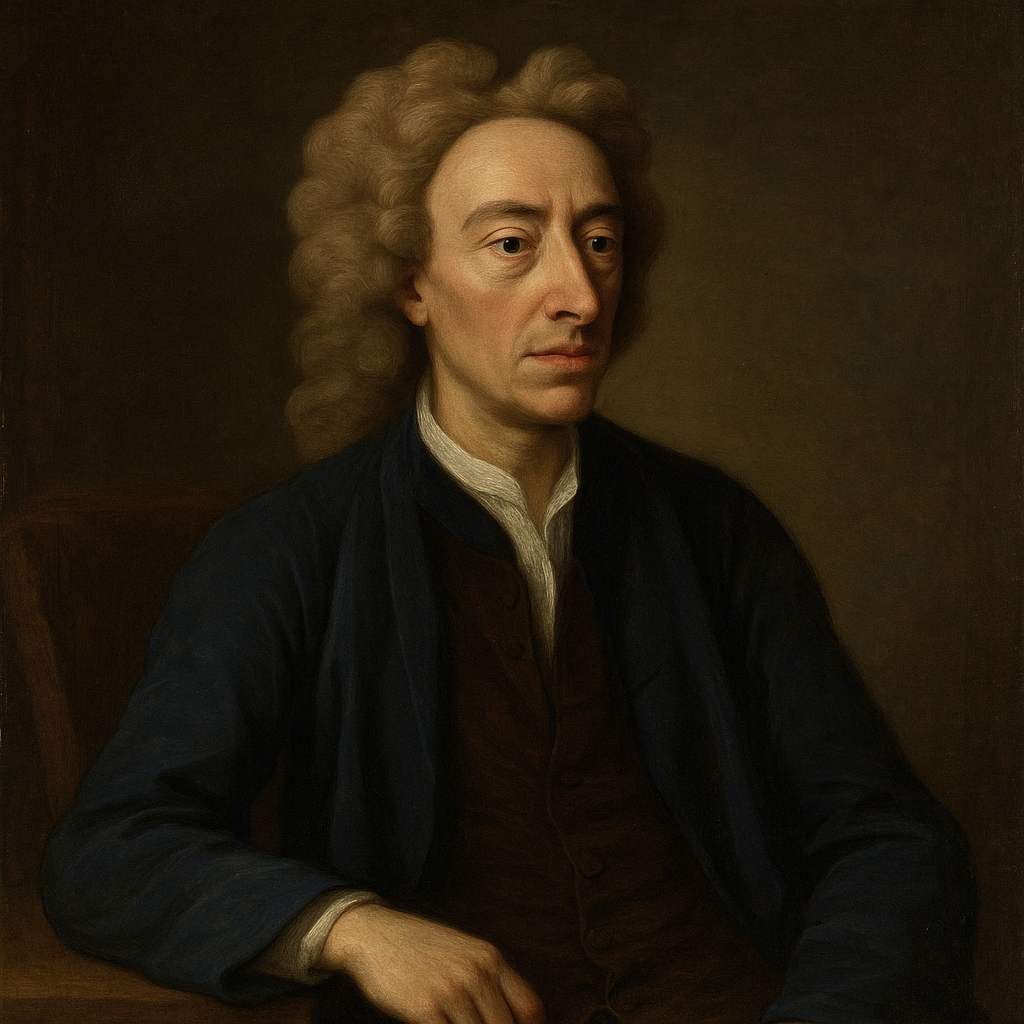

Alexander Pope

1688 to 1744

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

Happy the man, whose wish and care

A few paternal acres bound,

Content to breathe his native air,

In his own ground.

Whose herds with milk, whose fields with bread,

Whose flocks supply him with attire,

Whose trees in summer yield him shade,

In winter fire.

Blest, who can unconcern'dly find

Hours, days, and years slide soft away,

In health of body, peace of mind,

Quiet by day.

Sound sleep by night; study and ease,

Together mix'd; sweet recreation;

And innocence, which most does please

With meditation.

Thus let me live, unseen, unknown,

Thus unlamented let me die,

Steal from the world, and not a stone

Tell where I lie.

Alexander Pope's Ode on Solitude

Introduction

Alexander Pope's "Ode on Solitude," written when the poet was merely twelve years old, stands as a remarkable testament to both precocious talent and the enduring appeal of pastoral meditation in English poetry. Despite its apparent simplicity, the poem presents a complex meditation on contentment, mortality, and the relationship between individual fulfillment and societal engagement. This analysis will explore how Pope's early masterpiece employs classical forms and themes while anticipating the concerns that would dominate his later work.

Form and Structure

The poem's structure reflects both its thematic concerns and Pope's early mastery of poetic technique. Composed of five quatrains, each following a consistent rhyme scheme (ABAB) with the fourth line of each stanza deliberately shortened, the poem creates a sense of containment that mirrors its central theme of bounded contentment. The shorter fourth lines serve multiple purposes: they create a musical cadence that suggests peaceful resolution, they visually represent the "few paternal acres bound" that the poem celebrates, and they provide a rhythmic constraint that paradoxically enables freedom within limitation—a central theme of the work.

Classical and Contemporary Influences

The influence of Horace's "Beatus ille" tradition is evident throughout the poem, yet Pope transforms this classical model in distinctly English ways. The phrase "Happy the man" directly echoes Horace's "Beatus ille qui procul negotiis" ("Happy is he who, far from business cares"), but Pope's treatment is more intimately domestic. Where classical predecessors often emphasized complete withdrawal from society, Pope's persona maintains a connection to inherited land ("paternal acres") and agricultural production, suggesting a more nuanced relationship with society and tradition.

The Economics of Contentment

One of the poem's most sophisticated aspects is its treatment of economic sufficiency. The second stanza presents a complete economic ecosystem: "Whose herds with milk, whose fields with bread, / Whose flocks supply him with attire." This is not mere pastoral decoration but a careful delineation of a sustainable economic model. The repetition of "whose" creates a litany of possession that paradoxically celebrates limited ownership. Pope's ideal is not poverty but sufficiency—a middle state that would later become central to his philosophical and satirical works.

Temporal and Spatial Dynamics

The poem's treatment of time reveals sophisticated philosophical undertones. The phrase "Hours, days, and years slide soft away" presents time not as a threatening force but as a gentle current. This connects to the spatial metaphors throughout the poem: the bounded acres, the shade of trees, the final unmarked resting place. Together, these create a complex meditation on how human consciousness exists within both temporal and spatial constraints.

The Ethics of Withdrawal

Perhaps the most philosophically challenging aspect of the poem lies in its final stanza: "Thus let me live, unseen, unknown." This raises profound questions about the relationship between individual contentment and social responsibility. Is Pope advocating a form of ethical egoism, or does the very act of writing and publishing such sentiments create a productive tension between withdrawal and engagement? The suggestion that the speaker wishes to "Steal from the world" implies both culpability and subtle criticism of the very withdrawal being described.

Linguistic Artifice and Natural Simplicity

A close reading reveals Pope's masterful balance between artificial construction and natural expression. Consider the line "Content to breathe his native air." The word "content" carries both its meaning of satisfaction and its root meaning of containment, while "native air" suggests both birthright and natural simplicity. This sophisticated wordplay appears throughout the poem, belying its surface simplicity.

Christian and Secular Tensions

The poem's treatment of meditation and innocence in the fourth stanza introduces a fascinating tension between Christian and secular virtues. The combination of "study and ease" suggests a classical otium, while "innocence" and "meditation" evoke Christian contemplative tradition. Pope's synthesis of these traditions creates a unique perspective on spiritual fulfillment that neither fully embraces nor fully rejects either tradition.

The Question of Biography

While it would be reductive to read the poem purely as biographical statement, its composition by such a young poet raises intriguing questions about prodigy and poetic identity. The mature control of form and sophisticated handling of classical themes suggest either remarkable intuitive understanding or careful study of poetic tradition, likely both. The poem's speaker adopts the persona of one contemplating death, creating a complex irony given the poet's youth.

Conclusion

"Ode on Solitude" reveals itself as far more than a simple pastoral fantasy or youthful imitation of classical models. Through careful control of form, sophisticated handling of philosophical themes, and subtle manipulation of multiple literary traditions, the poem achieves a complexity that rewards continued study. Its exploration of the relationship between constraint and freedom, withdrawal and engagement, and individual and society anticipates many of the central concerns of eighteenth-century thought while maintaining relevance for contemporary readers. The poem's enduring appeal lies not merely in its surface celebration of rural retirement but in its sophisticated engagement with fundamental questions of human fulfillment and social responsibility.

The fact that such a young poet could create a work of this complexity suggests either that we must reevaluate our understanding of poetic development or that certain fundamental human desires—for peace, for sufficiency, for meaningful withdrawal—transcend age and experience. In either case, "Ode on Solitude" stands as both a remarkable achievement in its own right and a fascinating precursor to Pope's mature work, worthy of continued critical attention and classroom study.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!