Thanatopsis

William Cullen Bryant

1794 to 1878

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

To him who in the love of nature holds

Communion with her visible forms, she speaks

A various language; for his gayer hours

She has a voice of gladness, and a smile

And eloquence of beauty, and she glides

Into his darker musings, with a mild

And healing sympathy, that steals away

Their sharpness, ere he is aware. When thoughts

Of the last bitter hour come like a blight

Over thy spirit, and sad images

Of the stern agony, and shroud, and pall,

And breathless darkness, and the narrow house,

Make thee to shudder, and grow sick at heart;—

Go forth, under the open sky, and list

To Nature's teachings, while from all around—

Earth and her waters, and the depths of air,—

Comes a still voice—

Yet a few days, and thee

The all-beholding sun shall see no more

In all his course; nor yet in the cold ground,

Where thy pale form was laid, with many tears,

Nor in the embrace of ocean, shall exist

Thy image. Earth, that nourished thee, shall claim

Thy growth, to be resolved to earth again,

And, lost each human trace, surrendering up

Thine individual being, shalt thou go

To mix for ever with the elements,

To be a brother to the insensible rock

And to the sluggish clod, which the rude swain

Turns with his share, and treads upon. The oak

Shall send his roots abroad, and pierce thy mould.

Yet not to thine eternal resting-place

Shalt thou retire alone—nor couldst thou wish

Couch more magnificent. Thou shalt lie down

With patriarchs of the infant world—with kings,

The powerful of the earth—the wise, the good,

Fair forms, and hoary seers of ages past,

All in one mighty sepulchre.—The hills

Rock-ribbed and ancient as the sun,—the vales

Sketching in pensive quietness between;

The venerable woods—rivers that move

In majesty, and the complaining brooks

That make the meadows green; and, poured round all,

Old ocean's gray and melancholy waste,—

Are but the solemn decorations all

Of the great tomb of man. The golden sun,

The planets, all the infinite host of heaven,

Are shining on the sad abodes of death,

Through the still lapse of ages. All that tread

The globe are but a handful to the tribes

That slumber in its bosom.—Take the wings

Of morning—and the Barcan desert pierce,

Or lose thyself in the continuous woods

Where rolls the Oregan, and hears no sound,

Save his own dashings—yet—the dead are there:

And millions in those solitudes, since first

The flight of years began, have laid them down

In their last sleep—the dead reign there alone.

So shalt thou rest—and what if thou withdraw

Unheeded by the living—and no friend

Take note of thy departure? All that breathe

Will share thy destiny. The gay will laugh

When thou art gone, the solemn brood of care

Plod on, and each one as before will chase

His favourite phantom; yet all these shall leave

Their mirth and their employments, and shall come,

And make their bed with thee. As the long train

Of ages glide away, the sons of men,

The youth in life's green spring, and he who goes

In the full strength of years, matron, and maid,

And the sweet babe, and the gray-headed man,—

Shall one by one be gathered to thy side,

By those, who in their turn shall follow them.

So live, that when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, that moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave,

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.

William Cullen Bryant's Thanatopsis

Introduction

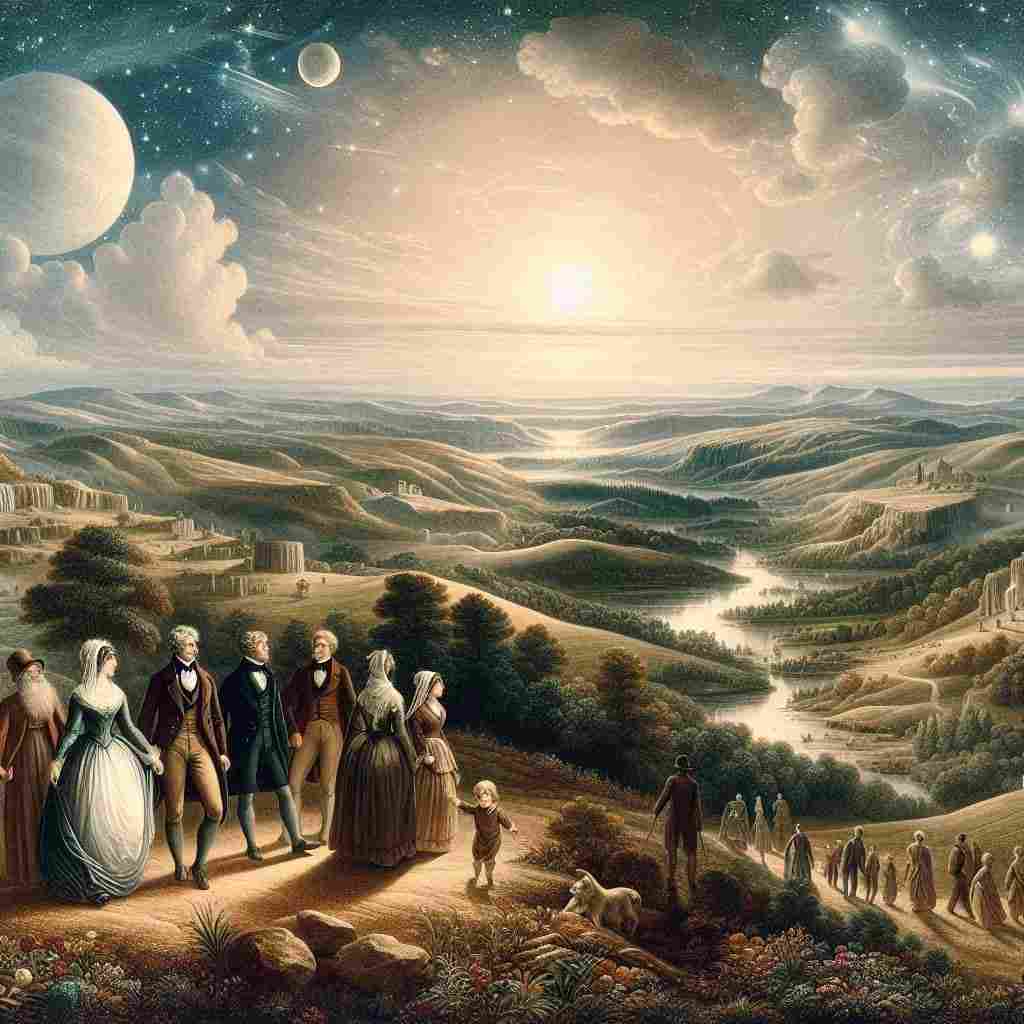

William Cullen Bryant's "Thanatopsis," first published in 1817, stands as a seminal work in American Romantic poetry, offering a profound meditation on death and humanity's relationship with nature. The poem, whose title translates from Greek as "a view of death," presents a complex interweaving of themes that challenge conventional notions of mortality and offer a uniquely American perspective on the human condition. This essay will explore the multifaceted layers of Bryant's masterpiece, examining its philosophical underpinnings, literary techniques, and cultural significance within the context of early 19th-century American literature.

Thematic Analysis

At its core, "Thanatopsis" grapples with the universal human fear of death, proposing a perspective that seeks to reconcile this anxiety with the eternal cycles of nature. Bryant's approach is notable for its departure from traditional Christian narratives of afterlife, instead offering a view that is more pantheistic and grounded in the natural world. The poem begins by personifying Nature as a comforting maternal figure, one who "speaks / A various language" to those who commune with her. This personification serves to establish an intimate connection between humanity and the natural world, setting the stage for the poem's central argument.

The poet's treatment of death is both unflinching and consolatory. He acknowledges the "sad images / Of the stern agony, and shroud, and pall, / And breathless darkness, and the narrow house" that often accompany thoughts of mortality. However, rather than dwelling on these grim aspects, Bryant redirects the reader's attention to the broader context of nature's eternal cycle. The assertion that one will "mix for ever with the elements, / To be a brother to the insensible rock / And to the sluggish clod" presents death not as an end, but as a transformation and reintegration into the natural world.

This theme of interconnectedness is further developed through the poem's expansive temporal and spatial scope. Bryant invokes "patriarchs of the infant world" and "kings, / The powerful of the earth" to emphasize the universality of death across time and social strata. Similarly, his references to diverse geographical features—from "the Barcan desert" to "the continuous woods / Where rolls the Oregan"—create a sense of death's omnipresence across the globe. This vast perspective serves to diminish the individual's fear of death by contextualizing it within the grand scale of natural and human history.

Literary Techniques and Style

Bryant's mastery of form and language is evident throughout "Thanatopsis." The poem is written in blank verse, employing unrhymed iambic pentameter that lends it a solemn, meditative rhythm reminiscent of Shakespearean soliloquies. This choice of form allows Bryant to maintain a tone of dignified contemplation while exploring profoundly emotional themes.

The poet's use of imagery is particularly striking. He juxtaposes the ephemeral nature of human life with the enduring aspects of the natural world, as seen in lines like "The hills / Rock-ribbed and ancient as the sun,—the vales / Stretching in pensive quietness between." This contrast serves to humble the reader, placing human existence within a broader cosmic context.

Bryant's diction is carefully chosen to evoke both the beauty and the indifference of nature. Words like "melancholy," "solemn," and "pensive" create an atmosphere of quiet reflection, while phrases such as "insensible rock" and "sluggish clod" emphasize nature's impassivity. This tension between beauty and indifference is central to the poem's philosophical stance, suggesting that while nature may not mourn individuals, it provides a form of immortality through the cycle of decomposition and renewal.

The use of extended metaphors throughout the poem is particularly effective. The comparison of Earth to a "mighty sepulchre" adorned with natural "decorations" transforms the entire planet into a grand mausoleum, a concept that is both awe-inspiring and comforting. Similarly, the metaphor of death as an "innumerable caravan" in the poem's conclusion presents mortality as a communal journey rather than a solitary end.

Cultural and Literary Context

"Thanatopsis" emerged during a pivotal period in American literary history, as writers sought to establish a distinctly American voice independent of European traditions. Bryant's poem is significant in this context for its uniquely American perspective on nature and death. Unlike the more domesticated landscapes of English Romantic poetry, Bryant presents nature as vast, wild, and fundamentally alien to human concerns. This vision resonates with the American experience of the early 19th century, characterized by westward expansion and the confrontation with wilderness.

The poem's philosophical underpinnings draw from various sources, blending elements of Deism, Transcendentalism, and classical stoicism. The absence of explicit Christian imagery or references to a personal deity aligns with Deist thought, while the emphasis on nature as a source of spiritual insight prefigures Transcendentalist philosophy. The stoic acceptance of death and the emphasis on living virtuously in preparation for it ("So live, that when thy summons comes to join / The innumerable caravan...") echoes classical philosophers like Marcus Aurelius.

Bryant's work also reflects the influence of English Romantic poets, particularly William Wordsworth. The concept of nature as a source of comfort and wisdom is reminiscent of Wordsworth's "Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey." However, Bryant's tone is more somber and his vision of nature more impersonal, reflecting perhaps the harsher realities of the American wilderness.

Influence and Legacy

"Thanatopsis" had a profound impact on American literature, helping to establish a poetic tradition that was distinctly American in its themes and perspectives. The poem's blend of philosophical depth, emotional resonance, and natural imagery influenced subsequent generations of American poets, from Walt Whitman to Robert Frost.

The work's enduring popularity also speaks to its universal themes and the timeless quality of its message. In an era of increasing secularization, Bryant's non-denominational approach to mortality continues to offer solace and perspective to readers grappling with existential questions.

Conclusion

William Cullen Bryant's "Thanatopsis" stands as a masterpiece of American Romantic poetry, offering a profound meditation on mortality that continues to resonate with readers two centuries after its composition. Through its skillful blend of natural imagery, philosophical insight, and formal mastery, the poem presents a vision of death that is at once humbling and comforting. By situating human mortality within the vast cycles of nature, Bryant offers a perspective that transcends individual fear and anxiety, inviting readers to find peace in their connection to the natural world and the broader human experience. As such, "Thanatopsis" remains not only a significant literary achievement but also a powerful source of contemplation on the human condition, inviting each new generation of readers to engage with its timeless themes and find their own place within the "mighty sepulchre" of Earth.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more