The Village Blacksmith

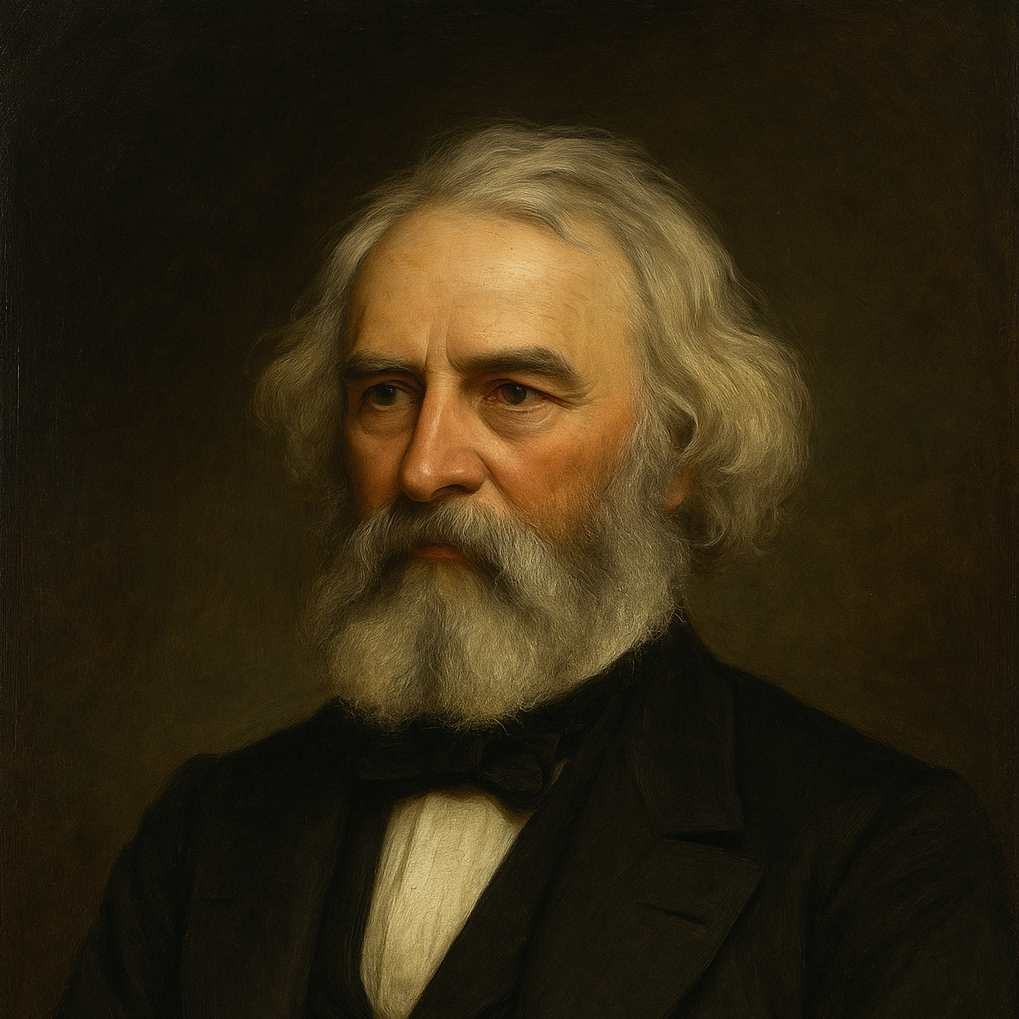

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

1807 to 1882

Under a spreading chestnut tree

The village smithy stands;

The Smith, a mighty man is he,

With large and sinewy hands;

And the muscles of his brawny arms

Are strong as iron bands.

His hair is crisp, and black, and long,

His face is like the tan;

His brow is wet with honest sweat,

He earns whate'er he can

And looks the whole world in the face

For he owes not any man.

Week in, week out, from morn till night,

You can hear his bellows blow;

You can hear him swing his heavy sledge,

With measured beat and slow,

Like a sexton ringing the village bell,

When the evening sun is low.

And children coming home from school

Look in at the open door;

They love to see the flaming forge,

And hear the bellows roar,

And catch the burning sparks that fly

Like chaff from a threshing floor.

He goes on Sunday to the church

and sits among his boys;

He hears the parson pray and preach.

He hears his daughter's voice

singing in the village choir,

And it makes his heart rejoice.

It sounds to him like her mother's voice,

Singing in Paradise!

He needs must think of her once more,

How in the grave she lies;

And with his hard, rough hand he wipes

A tear out of his eyes.

Toiling,--rejoicing,--sorrowing,

Onward through life he goes;

Each morning sees some task begin,

Each evening sees it close;

Something attempted, something done,

Has earned a night's repose.

Thanks, thanks to thee, my worthy friend

For the lesson thou hast taught!

Thus at the flaming forge of life

Our fortunes must be wrought;

Thus on its sounding anvil shaped

Each burning deed and thought!

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's The Village Blacksmith

Introduction

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's "The Village Blacksmith" stands as a quintessential example of 19th-century American poetry, embodying the ideals of hard work, perseverance, and moral integrity that characterized the nation's ethos during the Industrial Revolution. This poem, first published in 1840, offers a profound meditation on the dignity of labor and the cyclical nature of life, all framed within the microcosm of a small-town blacksmith's daily existence. Through its careful construction and evocative imagery, Longfellow creates a powerful narrative that resonates beyond its immediate context, touching upon universal themes that continue to captivate readers nearly two centuries later.

Structure and Form

The poem's structure is as methodical and rhythmic as the blacksmith's work itself. Composed of seven six-line stanzas, or sestets, the poem follows a consistent ABCBDB rhyme scheme. This regularity mirrors the steady, predictable nature of the blacksmith's life and work. The meter alternates between iambic tetrameter and iambic trimeter, creating a cadence that echoes the rise and fall of the blacksmith's hammer. This metrical choice is no mere coincidence; it serves to aurally reinforce the central motif of the poem - the blacksmith's ceaseless labor.

The sestets themselves can be seen as representative of the six working days of the week, with the final stanza serving as a reflection on the cumulative meaning of this labor, much as Sunday provides a day of rest and contemplation. This structural choice underscores the poem's themes of cyclical time and the sanctity of work.

Imagery and Symbolism

Longfellow's mastery of imagery is evident from the opening lines, where the "spreading chestnut tree" serves as both a literal backdrop for the smithy and a metaphorical representation of strength, endurance, and shelter. The tree, like the blacksmith, stands as a pillar of the community, deeply rooted and providing shade and stability.

The blacksmith himself is described in terms that blur the line between man and the materials he works with. His hands are "large and sinewy," his arms "strong as iron bands." This conflation of the human and the metallic serves to emphasize the symbiotic relationship between the craftsman and his craft. The smith shapes the metal, but in turn, the work shapes him, both physically and metaphorically.

The imagery of fire and forge recurs throughout the poem, serving multiple symbolic functions. On one level, it represents the transformative power of labor - raw materials are reshaped into useful objects through the application of heat and skill. On another, it evokes biblical and mythological associations, casting the blacksmith as a quasi-divine figure, a creator in his own right. The "flaming forge" and "burning sparks" also foreshadow the poem's final stanza, where life itself is likened to a forge on which human destiny is shaped.

Themes of Labor and Virtue

Central to the poem is the celebration of honest labor. The blacksmith is presented as the epitome of the virtuous working man, his integrity as solid as the metal he forges. The line "He earns whate'er he can / And looks the whole world in the face / For he owes not any man" encapsulates the 19th-century ideal of self-reliance and financial independence. This portrayal resonates with the Puritan work ethic that still held sway in Longfellow's New England, as well as with the broader American value of rugged individualism.

Yet, the poem does not present labor as mere drudgery. There is a rhythm and beauty to the blacksmith's work, emphasized by the musical imagery of the "measured beat and slow" of his sledge, compared to the ringing of the "village bell." This auditory imagery suggests that labor, when performed with skill and dedication, can attain a kind of musicality, a harmony with the natural rhythms of life.

The Cycle of Life and Generational Continuity

Longfellow skillfully weaves the theme of life's cyclical nature throughout the poem. The daily routine of the blacksmith, the weekly pattern of work and worship, and the progression from childhood to adulthood are all depicted. The presence of the schoolchildren, fascinated by the smithy, suggests the passing on of knowledge and skills to the next generation.

The poignant moment when the blacksmith is reminded of his late wife by his daughter's singing introduces a note of sorrow, reminding the reader of the full spectrum of human experience. Yet even this grief is integrated into the overall rhythm of life, as the blacksmith wipes away his tear and continues his work. This juxtaposition of joy and sorrow, encapsulated in the line "Toiling,--rejoicing,--sorrowing," presents life as a complex tapestry of experiences, all given meaning through the continuity of labor and family.

Religious and Moral Dimensions

While not overtly religious, the poem is imbued with a sense of moral rectitude and spiritual significance. The blacksmith's Sunday church attendance and the imagery of his daughter's voice sounding like her mother's "Singing in Paradise" introduce a transcendent element to the otherwise earthly narrative. This suggests that the blacksmith's virtue is not merely secular but aligned with higher spiritual values.

Moreover, the final stanza's metaphor of life as a "flaming forge" where "fortunes must be wrought" and the "sounding anvil" where deeds and thoughts are shaped, elevates the blacksmith's mundane labor to a metaphysical plane. It implies that all of human existence is a process of forging character and destiny through our actions and choices.

Literary and Historical Context

"The Village Blacksmith" must be understood within the context of 19th-century American literature and the broader cultural movements of the time. The poem's idealization of rural life and honest labor aligns with the Romantic movement's glorification of the natural and the unspoiled. Yet, it also looks forward to the Transcendentalist emphasis on self-reliance and the inherent dignity of all work, themes that would be further developed by writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

Furthermore, the poem can be read as a response to the rapid industrialization occurring in America at the time. By focusing on a traditional craftsman, Longfellow presents a nostalgic view of pre-industrial labor, valorizing a way of life that was increasingly under threat from mechanization and mass production.

Conclusion

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's "The Village Blacksmith" is a masterful exploration of the intersections between labor, virtue, and the human experience. Through its carefully crafted structure, vivid imagery, and resonant themes, the poem elevates the ordinary to the extraordinary, finding profound meaning in the rhythms of daily life and work.

The enduring appeal of this poem lies in its ability to speak to fundamental human experiences and values. It reminds us of the dignity inherent in honest labor, the importance of community and family, and the way in which our daily actions shape our character and legacy. In the figure of the blacksmith, Longfellow has created an everyman hero, a symbol of the quiet strength and integrity that form the backbone of society.

As we continue to grapple with questions of work, worth, and meaning in an increasingly automated and digital age, "The Village Blacksmith" remains relevant, challenging us to consider the value of craftsmanship, the importance of connecting to our labor, and the ways in which we can forge our own destinies on the "sounding anvil" of life. In this way, Longfellow's poem transcends its 19th-century origins, continuing to resonate with readers and offer "lessons" that are as pertinent today as they were when first penned.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!