The Ghouls

Helen Hamilton

1882 to 1954

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

You strange old ghouls,

Who gloat with dulled old eyes,

Over those lists,

Those dreadful lists,

To see what name

Of friend of relation,

However distant,

May be appended

To your private Roll of Honour.

Unknowingly you draw, it seems,

From their young bodies,

Dead young bodies,

Fresh life,

New value,

Now that yours are ebbing.

You strange old ghouls,

Who gloat with dulled old eyes,

Over those lists,

Those dreadful lists,

Of young men dead.

Helen Hamilton's The Ghouls

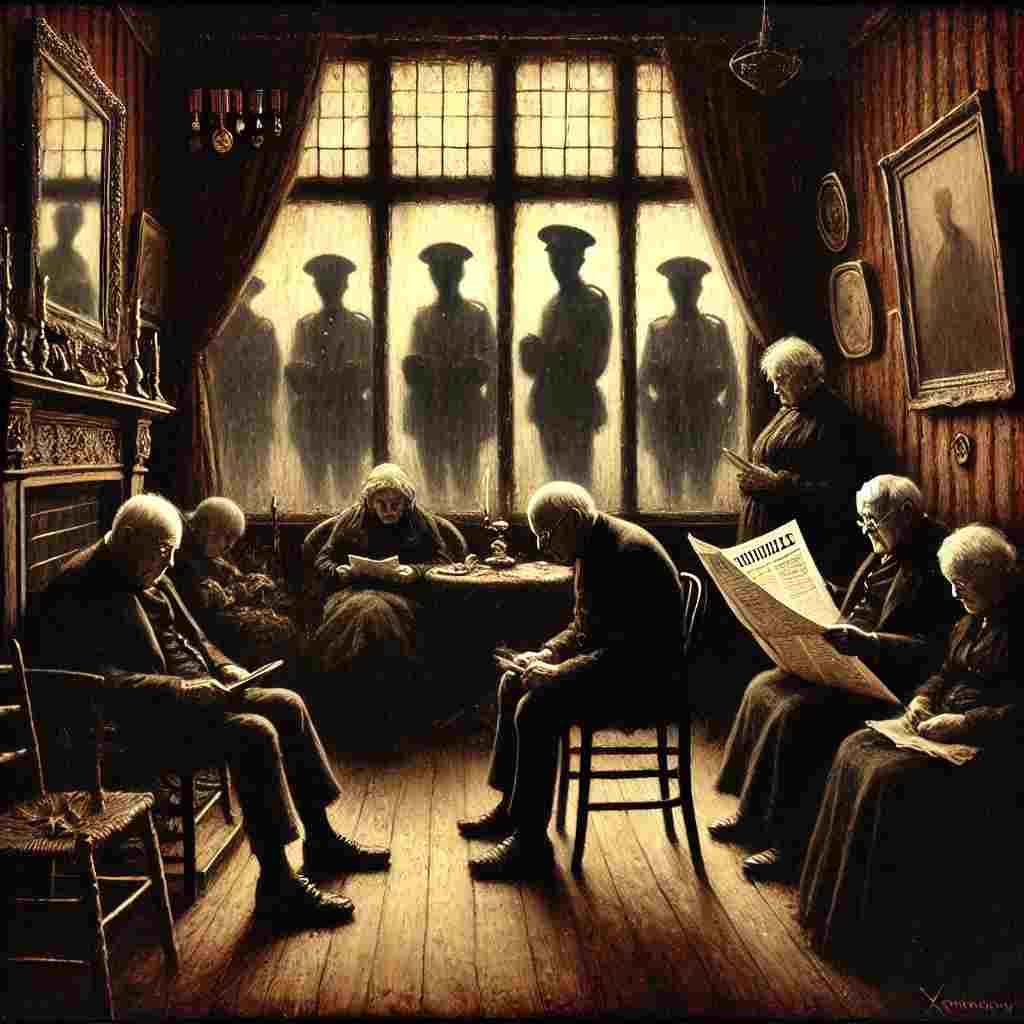

Helen Hamilton’s The Ghouls is a haunting and incisive poem that critiques the detachment and voyeuristic fascination with which some individuals observe the casualties of war. Written during or in the aftermath of World War I—a conflict that reshaped modern consciousness—the poem exposes the moral and emotional decay of those who derive a perverse satisfaction from the deaths of young soldiers. Through stark imagery, repetition, and biting irony, Hamilton crafts a work that is both a lament for the dead and an indictment of the living.

This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its use of literary devices, its central themes, and its emotional impact. Additionally, we will consider how The Ghouls fits within the broader tradition of war poetry, comparing it to works by Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, and examining its philosophical implications regarding grief, exploitation, and the ethics of remembrance.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate The Ghouls, one must situate it within the literary and historical landscape of World War I. The war, which lasted from 1914 to 1918, resulted in unprecedented carnage, with millions of young men slaughtered in trench warfare. The sheer scale of death forced societies to confront the brutal realities of modern combat, and many poets—particularly those who served—responded with works that oscillated between despair, anger, and disillusionment.

Helen Hamilton, though less widely known than male war poets like Owen or Sassoon, contributed to this tradition with a distinctly feminist perspective. Her work often scrutinized the roles of non-combatants—particularly those on the home front—who engaged in what she perceived as a grotesque fascination with war’s casualties. The Ghouls captures this sentiment, portraying elderly individuals (likely civilians) who pore over casualty lists not in mourning, but with a ghoulish hunger.

The poem’s title itself is significant. Ghouls, in folklore, are creatures that feed on the dead, and Hamilton weaponizes this metaphor to critique those who derive a vicarious thrill from war’s tragedies. The act of reading casualty lists—a common practice during the war—becomes not an act of remembrance, but one of vampiric consumption.

Literary Devices and Structure

Hamilton employs several key literary devices to reinforce her critique and deepen the poem’s emotional resonance.

1. Repetition and Incantatory Rhythm

The poem’s repetitive structure—particularly the phrases “You strange old ghouls” and “Over those lists, / Those dreadful lists”—creates a hypnotic, almost accusatory rhythm. This repetition mimics the obsessive behavior of the ghouls themselves, who return again and again to the names of the dead. The circularity of the poem’s structure suggests a never-ending cycle of voyeuristic consumption, reinforcing the idea that war’s spectators are trapped in a morbid ritual.

2. Diction and Imagery

Hamilton’s word choices are deliberately stark. The “dulled old eyes” of the ghouls suggest not only physical aging but moral decay. Their gaze is not sharp with grief but “dulled”—perhaps by years of desensitization or by the sheer banality of death in wartime. The lists are not merely sad or tragic; they are “dreadful,” a word that carries connotations of both horror and inevitability.

The phrase “Dead young bodies” is particularly jarring. The bluntness of “dead” followed by “young” underscores the unnaturalness of youthful death in war. The contrast between “young bodies” and the ghouls’ own “ebbing” lives reinforces the idea that the old feed on the vitality of the young, both literally (in the sense of war consuming youth) and metaphorically (in the sense of deriving emotional sustenance from others’ suffering).

3. Irony and Satire

The poem’s tone is deeply ironic. The phrase “private Roll of Honour” is particularly biting—a “Roll of Honour” traditionally commemorates the brave, but here it is perverted into a personal tally of the dead, kept not out of reverence but out of a macabre fascination. The ghouls “Unknowingly” draw life from the dead, suggesting that their behavior is not fully conscious, yet no less grotesque for its obliviousness.

Hamilton’s satire aligns her with poets like Siegfried Sassoon, whose “The Glory of Women” similarly critiques the home front’s romanticization of war. Both poets expose the hypocrisy of those who claim to honor the dead while remaining emotionally detached from the reality of their suffering.

Themes

1. The Exploitation of the Dead

Central to The Ghouls is the idea that the dead are being used—not just by the machinery of war, but by those who claim to mourn them. The ghouls “gloat” over the lists, suggesting a kind of pleasure in the act. This theme resonates with Wilfred Owen’s “Anthem for Doomed Youth,” which critiques the empty rituals of mourning. However, while Owen focuses on the absence of proper remembrance, Hamilton focuses on the perversion of remembrance into something self-serving.

2. Generational Conflict

The poem underscores a stark divide between the young, who die, and the old, who survive and feed on their deaths. This generational tension was a recurring concern in post-war literature, reflecting broader societal anxieties about the sacrifices demanded of youth. The ghouls’ “ebbing” lives contrast with the “fresh life” they extract from the dead, suggesting a vampiric relationship between the generations.

3. Desensitization and Moral Decay

The ghouls’ “dulled old eyes” imply a loss of moral clarity. War has not only killed the young but eroded the humanity of those who observe it from a distance. This idea aligns with modernist anxieties about the dehumanizing effects of industrialized warfare, a theme explored in T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and other works of the period.

Emotional Impact

The Ghouls is a poem of quiet fury. Unlike Owen’s visceral depictions of trench warfare, Hamilton’s critique is colder, more controlled, but no less devastating. The absence of overt sentimentality makes the poem’s indictment even more powerful—the ghouls are not caricatures, but plausible figures, making their behavior all the more unsettling.

The emotional core of the poem lies in its contrast between the dead’s lost potential and the ghouls’ hollow fascination. The “young bodies” are not just dead; they are “fresh,” a word that heightens the sense of waste. The poem forces the reader to confront uncomfortable questions: Who truly mourns the dead? And who uses them for their own purposes?

Comparative and Philosophical Perspectives

Hamilton’s poem can be fruitfully compared to other war poets. Like Sassoon’s “They,” which contrasts the idealized rhetoric of war with its grim reality, The Ghouls exposes hypocrisy. However, while Sassoon often directs his anger at institutions (the church, the state), Hamilton targets individuals—specifically, the passive spectators of war.

Philosophically, the poem engages with the ethics of grief. Is it possible to mourn authentically in a world where death has been commodified? The ghouls’ behavior suggests not—their mourning is performative, even parasitic. This aligns with Theodor Adorno’s later assertion that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric”—the idea that art risks aestheticizing suffering. Hamilton seems to ask: Does even the act of reading casualty lists risk becoming another form of consumption?

Conclusion

The Ghouls is a masterful work of wartime critique, blending sharp satire with profound sorrow. Through its incisive imagery, rhythmic intensity, and unflinching moral gaze, the poem forces readers to confront the uncomfortable ways in which societies process mass death. Hamilton’s voice—less celebrated than those of her male contemporaries—is nonetheless vital, offering a perspective that is both deeply personal and universally resonant.

In an age where war’s casualties are still often reduced to statistics or political talking points, The Ghouls remains disturbingly relevant. It asks us: Who are the real ghouls? And how do we ensure that our remembrance of the dead is an act of respect, not exploitation? These questions linger long after the poem’s final lines, a testament to its enduring power.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more