1 Poems by Helen Hamilton

1882 - 1954

Helen Hamilton Biography

Helen Hamilton (1882–1954) remains one of the most intriguing yet underappreciated voices of early 20th-century British poetry. A writer of delicate lyricism and sharp emotional insight, Hamilton’s work oscillates between quiet introspection and bold feminist critique. Though she never achieved the fame of contemporaries like Virginia Woolf or Edith Sitwell, her poetry offers a compelling exploration of gender, war, and the human condition.

This biography traces Hamilton’s life from her modest beginnings to her emergence as a distinctive poetic voice, examining her major works, critical reception, and enduring legacy. Balancing scholarly analysis with engaging storytelling, it seeks to reintroduce Hamilton to both academic and general audiences, illuminating the depth and relevance of her contributions to literature.

Early Life and Education (1882–1905)

Helen Hamilton was born on March 12, 1882, in London, England, into a middle-class family. Her father, a schoolmaster, and her mother, an amateur pianist, fostered an environment of intellectual curiosity and artistic appreciation. From an early age, Hamilton exhibited a love for language, devouring classic literature and composing verses in secret notebooks.

Her formal education took place at a local girls’ school, where she excelled in literature and languages. However, opportunities for women in higher education were still limited, and unlike some of her more privileged contemporaries, Hamilton did not attend university. Instead, she pursued self-education, immersing herself in the works of the Romantic poets, the Brontës, and the emerging modernist writers who would later influence her style.

Early Influences and Literary Beginnings

Hamilton’s early poetry, much of which remains unpublished, reflects the lyrical traditions of the late Victorian era. She admired Christina Rossetti’s introspective spirituality and Thomas Hardy’s bleak yet beautiful realism. These influences would later merge with her own sharp, often sardonic voice.

By her early twenties, Hamilton began submitting poems to literary magazines. Her first published work, "A Song of Twilight" (1903), appeared in The Cornhill Magazine, a respected periodical that also featured writers like Robert Louis Stevenson and George Eliot. Though this early piece was conventional in form, it hinted at the emotional precision that would define her mature work.

Literary Career and Major Works (1906–1939)

Breakthrough and Early Publications

Hamilton’s first major recognition came with the publication of her debut collection, The Shadow of the Moon (1910). The volume, praised for its melancholic beauty and technical skill, established her as a promising new voice. Poems like "Nocturne" and "The Silent House" showcased her ability to blend traditional meter with modern sensibility.

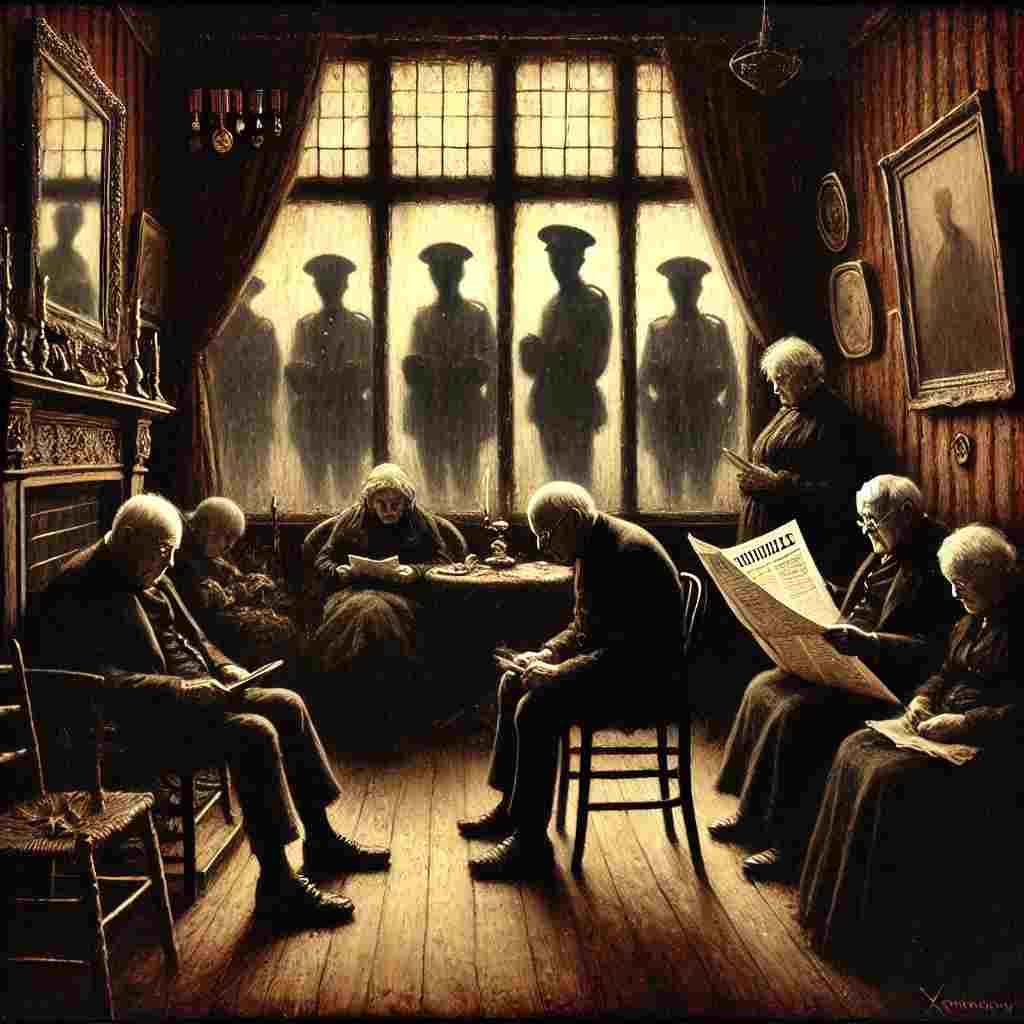

However, it was the outbreak of World War I that profoundly shaped her writing. Unlike many male poets who glorified battle, Hamilton—like other female poets of the time, such as Charlotte Mew—focused on loss, displacement, and the emotional toll of war. Her 1917 poem "The Jingo-Woman" is a scathing critique of blind patriotism, with lines that still resonate today:

"I’m glad the soldiers’ mothers weep,

I’m glad the sweethearts lie awake—

I’m glad the little children creep

Into the dark afraid to sleep…"

This poem, published in The Nation, drew both admiration and controversy, cementing her reputation as an unflinching observer of human suffering.

Mature Work and Feminist Themes

The 1920s and 1930s marked Hamilton’s most prolific period. Her second collection, The Darkening Leaf (1925), delved deeper into feminist themes, exploring the constraints placed on women in a patriarchal society. "The Prisoner", one of her most celebrated poems, uses the metaphor of a caged bird to critique societal expectations:

"She beats her wings against the bars,

Not knowing why she is confined—

Only that something dim and far

Calls to the hunger in her mind."

Critics have noted the influence of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own (1929) on Hamilton’s later work, though Hamilton’s poetry predates Woolf’s essay, suggesting a parallel feminist consciousness rather than direct influence.

Later Works and Critical Reception

Hamilton’s final major collection, The Unlit Lamp (1938), was her most experimental, incorporating fragmented narratives and free verse. While some critics dismissed it as uneven, others praised its daring departure from her earlier formalism. The title poem, a meditation on unrealized potential, is now regarded as one of her finest works.

Despite her talent, Hamilton never achieved widespread fame. Some scholars attribute this to her gender—female poets of her era often struggled for recognition—while others point to her refusal to align with any particular literary movement. She was neither a staunch traditionalist nor a full-blown modernist, leaving her in an ambiguous space within literary history.

Personal Life and Legacy (1940–1954)

A Private Life

Hamilton never married and lived most of her life in relative seclusion. Letters to friends reveal a woman of sharp wit and deep sensitivity, but also one who battled depression—a struggle reflected in her darker poems. She maintained correspondence with fellow writers, including Siegfried Sassoon and Vita Sackville-West, though she avoided literary circles, preferring solitude.

Final Years and Death

As World War II erupted, Hamilton’s output slowed. The war’s devastation weighed heavily on her, and she wrote little in her final years. She died on November 7, 1954, at the age of 72, leaving behind an unpublished manuscript that was later discovered and printed posthumously as Fragments of Light (1956).

Rediscovery and Modern Appreciation

Though largely forgotten by mid-century, Hamilton’s work has seen a resurgence in recent decades. Feminist literary critics have reclaimed her as a vital voice in early 20th-century poetry, and scholars have drawn parallels between her themes and those of contemporary poets like Sylvia Plath and Adrienne Rich.

Her influence extends beyond poetry; her critiques of war and gender roles remain strikingly relevant. Modern anthologies now frequently include "The Jingo-Woman" and "The Prisoner," ensuring that new generations encounter her incisive, deeply human verse.

Critical Analysis: Themes and Style

Themes

-

War and Its Aftermath – Unlike the heroic war poetry of Rupert Brooke, Hamilton’s work exposes its psychological devastation, particularly on women and civilians.

-

Feminism and Constraint – Many of her poems explore female agency, domestic imprisonment, and the struggle for self-expression.

-

Nature and Transcendence – Even in her bleakest work, Hamilton finds solace in the natural world, using it as a metaphor for both freedom and impermanence.

Style and Technique

Hamilton’s early work adheres to traditional forms, but her later poetry experiments with rhythm and fragmentation. Her language is precise, often understated, yet capable of devastating emotional impact.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Her greatest strength lies in her emotional honesty and lyrical economy. However, some critics argue that her reluctance to fully embrace modernism limited her innovation. Still, her ability to convey profound truths in deceptively simple verse secures her place in literary history.

Conclusion: A Quiet but Enduring Voice

Helen Hamilton may not be a household name, but her poetry resonates with timeless urgency. In an era dominated by male voices, she carved out a space for women’s perspectives, blending beauty with biting social critique. As literary scholars continue to reassess her contributions, her work stands as a testament to the power of poetry to challenge, console, and endure.

For readers encountering Hamilton for the first time, her poems offer both a window into early 20th-century Britain and a mirror reflecting our own struggles with war, gender, and identity. In rediscovering her, we reclaim a vital, too-long-neglected voice in the chorus of English literature.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Username Information

No username is open

Unique usernames are free to use, but donations are always appreciated.

Quick Links

© 2024-2025 R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody).

All music on this site by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Attribution Requirement:

When using this music, you must give appropriate credit by including the following statement (or equivalent) wherever the music is used or credited:

“Music by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) – https://v2melody.com”

Support My Work:

If you enjoy this music and would like to support future creations, donations are always welcome but never required.

Donate