Come, Come, Whoever You Are (Persian)

Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī

1207 to 1273

بیا، بیا هر آنچه هستی بیا

بیا، بیا، هر آنچه هستی بیا

گر کافر و گبر و بتپرستی بیا

این درگه ما درگه نومیدی نیست

صد بار اگر توبه شکستی بیا

Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī's Come, Come, Whoever You Are

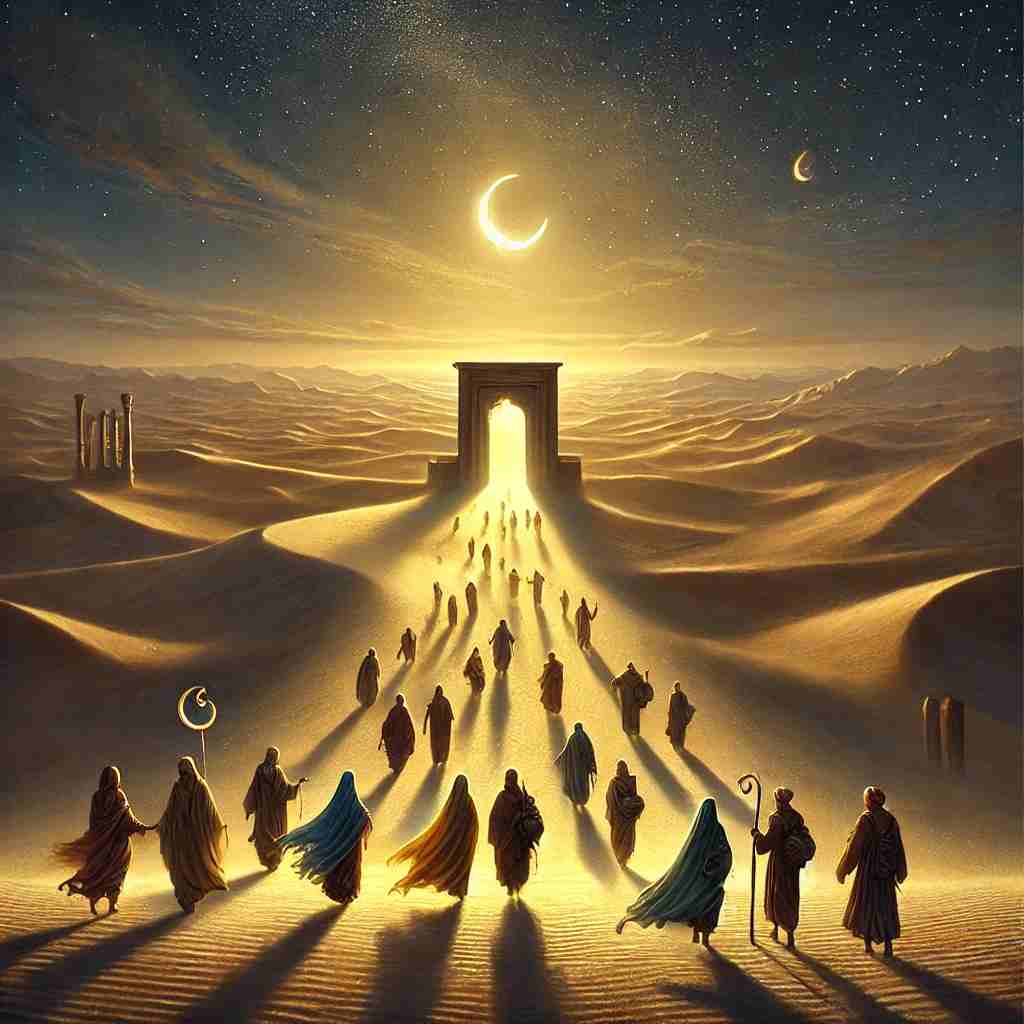

Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī’s short, yet profound poem "Come, Come, Whoever You Are" invites readers into an open, transcendent embrace, one that bridges boundaries of faith, character, and even failure. This work exemplifies Rūmī’s spiritual philosophy, grounded in Sufi mysticism, which emphasizes divine love, forgiveness, and inclusivity. Through a repetitive yet insistent invitation, Rūmī erases distinctions between individuals, urging unity in a journey toward divine understanding.

Analysis

-

“Come, come, whoever you are” / "بیا، بیا هر آنچه هستی بیا"

In this opening line, Rūmī’s repetition of the word “come” emphasizes an urgency and warmth in the call. The repetition acts almost like an echo, intensifying the sense of welcome. The phrase "whoever you are" reveals the unconditional nature of the invitation, as if to suggest that one's identity, creed, or life path is of no consequence. Rūmī embraces all, symbolizing the core Sufi belief that the divine is present within everyone and that human differences are irrelevant in the face of divine unity. -

"Wanderer, worshiper, lover of leaving, it doesn’t matter" / "گر کافر و گبر و بتپرستی بیا"

The Persian line here refers to "kaafar" (unbeliever), "gabr" (fire worshiper, often a term for Zoroastrians), and "bot-parast" (idolater), each representing different identities, often outside traditional Islam. In his translational interpretation, Coleman Barks replaces specific terms with archetypal roles such as "wanderer" and "lover of leaving," which capture the spirit of the verse while broadening its reach. Through this language, Rūmī calls to those outside the mainstream faith, emphasizing that divine acceptance is not bound by conventional religion or identity. It speaks to the non-judgmental essence of Sufism, which values the inward journey over outward forms. -

“Ours is not a caravan of despair” / "این درگه ما درگه نومیدی نیست"

This line is a reassurance that the path to the divine is welcoming and forgiving. The word "caravan" suggests a collective journey, resonant of ancient trade and pilgrimage routes, which were often long, arduous, and filled with fellowship. By stating that it is "not a caravan of despair," Rūmī seeks to lift the weight of past actions or failures from his followers. The phrase suggests that this spiritual journey transcends hopelessness and punishment; it is a path of hope, one that continually invites and forgives. -

“Even if you have broken your vows a hundred times” / "صد بار اگر توبه شکستی بیا"

Here, Rūmī acknowledges human frailty and the repeated breaking of vows, which could refer to lapses in faith, sin, or personal failures. Rather than condemning, Rūmī opens the door even wider, suggesting that divine love and forgiveness are not transactional or limited. The phrase "a hundred times" is symbolic of countless forgiveness, in line with Sufi ideals that see love as infinite. This idea of returning regardless of one’s repeated failings reaffirms the poem’s overarching theme of boundless compassion and inclusivity. -

“Come, come again, come.”

The final line reiterates the invitation with even greater insistence. The structure mimics a chant or prayer, as if the repeated words themselves might transport the listener into a spiritual state of acceptance and peace. This repetition reinforces the open-ended nature of the invitation—there is no final cutoff, no point beyond which one is unwelcome. The poem thus ends with an image of limitless grace, reminiscent of a flowing river to which anyone can return.

Conclusion

Rūmī’s "Come, Come, Whoever You Are" is a powerful, succinct articulation of Sufi values: the transcendence of religious and social labels, the boundless nature of divine love, and the perpetual opportunity for redemption and spiritual communion. By centering the human yearning for connection with the divine, Rūmī’s words offer solace and inclusivity. His call is both a reminder and a reassurance that, in the divine realm, every seeker has a place—no matter their past, identity, or beliefs. This enduring message of inclusivity and forgiveness continues to resonate, underscoring the universality and timelessness of Rūmī’s spiritual insights.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!