1 Poems by Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī

1207 - 1273

Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī Biography

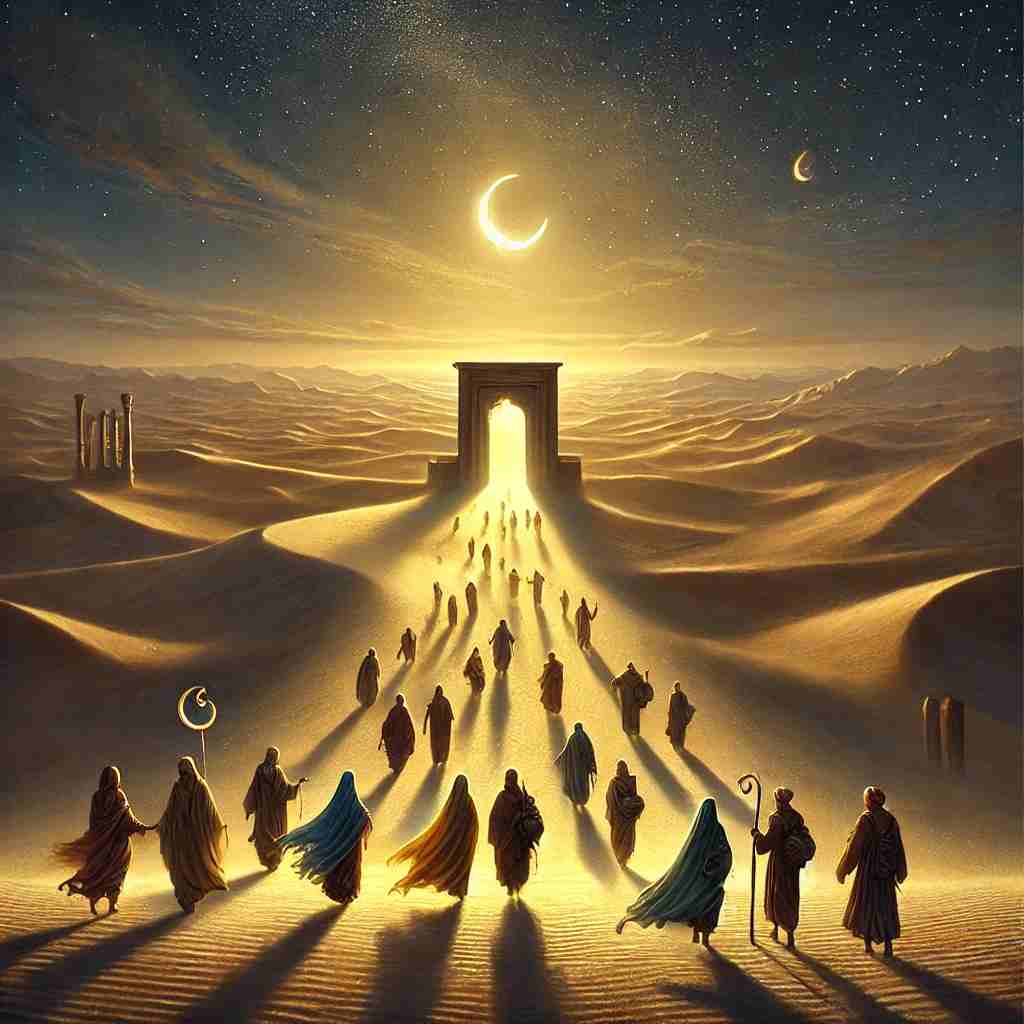

Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, widely known as Rumi in the West, stands as one of the most beloved and influential mystical poets in world literature. Born on September 30, 1207, in the Persian city of Balkh (in present-day Afghanistan) and later settling in Konya (present-day Turkey), Rumi’s works have transcended borders, cultures, and religions. His poems, especially those within his seminal works, the Masnavi and Divan-e Shams-e Tabrizi, have left an enduring legacy that continues to captivate and inspire readers from all walks of life. Often recognized for his profound and universal spirituality, Rumi's poetry transcends the doctrinal, aiming instead to explore the depths of the human soul, love, and the divine.

Rumi's life was marked by considerable upheaval and transformation, both personal and cultural. Born into a family of esteemed scholars and mystics, Rumi’s early years unfolded during a time of social and political instability in the Persian Empire. His father, Baha al-Din Walad, a prominent scholar and preacher, was known for his teachings on spiritual matters and his own mystical tendencies, which would become influential in shaping Rumi’s early worldview. The family fled Balkh around 1215 to escape the advancing Mongol invasions, a displacement that took them on an extended journey through the Islamic world, stopping in Nishapur, Baghdad, and Mecca, before eventually settling in Konya. This journey exposed young Rumi to diverse cultures, spiritual practices, and philosophical ideas, planting the seeds for the expansiveness that would later characterize his thought and poetry.

In Nishapur, Rumi encountered the renowned Sufi poet and mystic Farid al-Din Attar, who is said to have recognized in the young boy an extraordinary spiritual potential. Attar even gave him a copy of his own book, Asrar Nama (The Book of Secrets), which likely had a profound influence on Rumi’s burgeoning mystical inclinations. The experience with Attar would be one of Rumi’s earliest introductions to the rich tradition of Persian Sufi poetry, and it hinted at the trajectory his life would take as a seeker, poet, and spiritual leader.

After the death of his father in 1231, Rumi inherited his father’s position as a respected Islamic teacher in Konya, where he soon developed a reputation as a prominent religious scholar and jurist. Though a diligent student and teacher of traditional Islamic theology and jurisprudence, his mystical interests continued to deepen over the years. During this period, Rumi’s days were devoted to his duties as a teacher, and he gathered a considerable following among students and admirers who sought to learn from his knowledge and insight. However, despite his religious and intellectual prominence, Rumi was not yet the mystical poet we now know; his transformation into a poet of divine love and transcendent union was yet to come.

The turning point in Rumi’s life came in 1244 with the arrival of the enigmatic mystic Shams-e Tabrizi, an event that Rumi himself would describe as nothing short of spiritual awakening. Shams was an itinerant dervish, known for his unconventional wisdom, passionate spirituality, and often unorthodox views that made him both loved and resented in equal measure. His encounter with Rumi was seismic; the two men formed a deep, spiritual bond that would last for only a few short years but would forever alter the course of Rumi's life and work. For Rumi, Shams became a mirror and catalyst, igniting an intense longing and devotion that defied conventional description. Shams challenged Rumi to confront his own understanding of God, love, and existence, steering him away from the rigid scholarship of formal theology and into the boundless realms of mystical experience.

The relationship between Rumi and Shams was not only deeply personal but also radically transformative for Rumi’s poetry and thought. For Rumi, Shams was not merely a friend or a teacher; he was a manifestation of divine love itself, a doorway to the mysteries of the universe. Shams opened Rumi to a love that transcended all worldly attachments and limitations, one that pulsed with the same energy that Rumi would later describe as animating all of creation. Under Shams’ influence, Rumi began to compose verses of unparalleled emotional intensity and spiritual insight, marking the start of a prolific period of poetic output. This relationship, however, was fraught with challenges; the intensity of Rumi’s bond with Shams drew criticism and envy from Rumi's followers, who did not fully comprehend the nature of their spiritual union. In 1247, Shams disappeared—likely murdered by followers resentful of his hold over Rumi. The loss devastated Rumi, plunging him into a profound grief that would fuel some of his most enduring poetry. Shams’ absence did not sever Rumi’s connection to him; instead, it drove him to seek Shams inwardly, within his own soul, as he transformed his longing and heartbreak into a creative force.

This loss of Shams became the impetus for Rumi’s Divan-e Shams-e Tabrizi, a monumental collection of ghazals, or lyrical poems, dedicated to Shams as a symbol of divine love. The Divan reflects the agony of separation, the ecstasy of union, and the relentless search for spiritual oneness. Rumi's ghazals are intensely personal yet universally resonant, as they probe the depths of human longing and love’s transcendent nature. In the ghazals, love becomes a cosmic force that dissolves all duality and boundaries, uniting the lover and the beloved, the seeker and the sought. Shams, the inspiration for these poems, becomes both an earthly beloved and a metaphor for God, the ultimate beloved. Through the Divan, Rumi not only mourns the physical absence of Shams but also celebrates the eternal presence of divine love that Shams had awakened within him.

The later years of Rumi’s life saw the creation of his other magnum opus, the Masnavi, a six-volume spiritual epic often referred to as the “Qur’an in Persian.” Unlike the lyrical and often esoteric nature of the Divan, the Masnavi adopts a more narrative and didactic approach, using parables, fables, and allegories to illustrate Sufi wisdom and principles. In the Masnavi, Rumi guides readers through a journey of self-discovery and spiritual awakening, presenting stories that reveal the nature of the human soul and its relationship with the divine. The work delves into themes of love, forgiveness, humility, and the stripping away of ego to attain unity with God. Rumi’s storytelling is imbued with humor, compassion, and an acute understanding of the human condition, making it accessible to readers from various backgrounds and spiritual dispositions.

The Masnavi is also noteworthy for its linguistic and structural complexity, as Rumi weaves together Islamic philosophy, folklore, and his unique Sufi metaphysics into an intricate tapestry of verse. This work embodies the principles of Sufism that Rumi held dear: that the soul's journey to God is one of purification and surrender, of transcending the self and embracing love as a transformative force. Rumi's use of metaphor and allegory in the Masnavi reflects the Sufi tradition’s emphasis on unveiling hidden meanings, encouraging readers to look beyond literal interpretations and seek the spiritual truths that lie beneath.

Rumi’s influence on Persian literature and Sufi thought is immeasurable, but his impact has reached far beyond the boundaries of the Persian-speaking world. His poetry has been translated into countless languages, inspiring generations of readers across cultures, faiths, and ideologies. The universal themes of his work—love, longing, spiritual awakening—resonate with readers of diverse backgrounds. Rumi’s ability to articulate the ineffable aspects of the human experience, to give voice to the soul’s innermost yearnings, has made him a timeless figure, bridging the worlds of East and West, secular and sacred, inner and outer.

The rituals of the Mevlevi Order, or the Whirling Dervishes, which Rumi’s followers established after his death, provide a physical embodiment of his spiritual philosophy. This practice, which involves a spinning dance performed as a form of meditation and devotion, symbolizes the soul’s ascent toward the divine. The dance mimics the movements of celestial bodies and reflects the Sufi idea of annihilating the ego in the experience of divine love. Today, the Mevlevi Order continues to honor Rumi’s legacy through these ceremonies, maintaining a living connection to his teachings on love, humility, and the quest for unity.

Rumi’s legacy extends to the present day, where his poetry continues to captivate and inspire. In the 20th century, figures like Coleman Barks and others began to translate Rumi's poetry for Western audiences, emphasizing its universal spirituality and making it widely accessible. Barks’ versions of Rumi’s poetry, while controversial for their interpretive liberties, have brought Rumi's message of love and unity to an unprecedented global audience. Through these translations, Rumi has been embraced as a poet of love, spirituality, and personal transformation, a mystic who speaks to the heart of the human experience.

Rumi passed away on December 17, 1273, in Konya, where he was buried in a mausoleum that has since become a pilgrimage site for admirers of his work. Known as “Urs-e Rumi” or Rumi’s wedding night, the day of his death is commemorated by the Mevlevi Order as his reunion with the divine. This notion of death as a return to the Beloved encapsulates Rumi’s view of life, death, and the soul’s eternal journey. In his poetry, he wrote about death not as an end but as a fulfillment, a return to the divine source from which all love flows.

In the centuries since his death, Rumi’s poetry has been recited, sung, and celebrated in countless ways, testifying to the enduring power of his vision. His works remind readers of the beauty in transcending one’s limitations, in seeking the divine within and around, and in embracing love as the ultimate purpose of life. Rumi’s voice, like a beacon, continues to guide souls in their search for truth, unity, and inner peace.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Username Information

No username is open

Unique usernames are free to use, but donations are always appreciated.

Quick Links

© 2024-2025 R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody).

All music on this site by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Attribution Requirement:

When using this music, you must give appropriate credit by including the following statement (or equivalent) wherever the music is used or credited:

"Music by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) – https://v2melody.com"

Support My Work:

If you enjoy this music and would like to support future creations, donations are always welcome but never required.

Donate